By Juma Kwayera

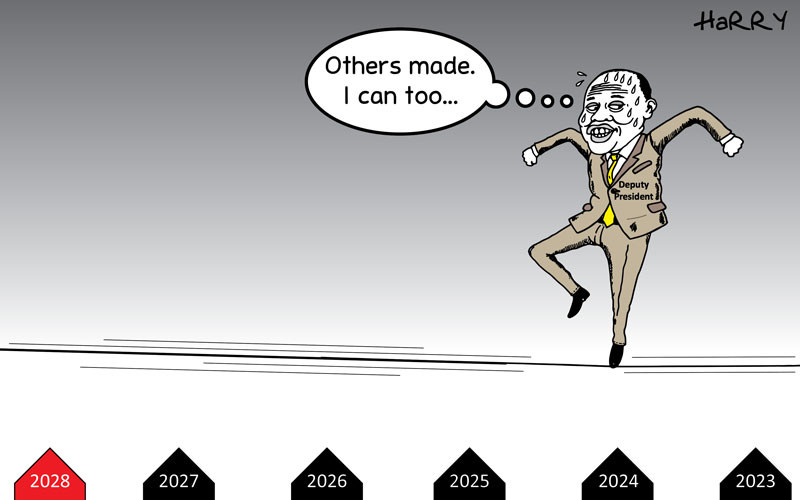

Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta, the flag-bearer for Jubilee Alliance is the proverbial reluctant horse that is pushed into the race screaming and kicking only to get accustomed to racing and become one of the top and most competitive horses.

His entry into the world of politics came through the hand of former President Moi propelling a hitherto publicity-shy Uhuru to a life in the limelight.

Uhuru is remembered by taxi-drivers who operate near Anniversary Towers as an easy going young man they shared cigarettes and sometimes, a tipple with.

They recall his hearty laughter and jovial power handshakes, which made him fit in a crowd of ‘commoners’ although born a ‘prince’.

Involvement in politics has changed all that.

The story of Uhuru political ascension bears strong similarities with Michael Corleone in the epic novel The Return of the Godfather, who initially is scoffed at as a weakling by friends of his father Vito Carleone, returns to torment them after the assassination of Vito.

Michael was more determined and vicious in his fight for the control and expansion of family business empire, traits Uhuru demonstrated in his ascendance to the political helm.

Former Kanu top brass seize every opportunity to remind Uhuru that they picked and dusted him in preparation for a career in politics. But by deed and planning, he has demonstrated he is his own man capable of running his own show.

Political flop

His initial entry into politics came through his election as the chairman of Gatundu sub-branch of Kanu in 1997.

It was with the tacit approval of Moi, who apparently had keen interest on passing the mantle of leadership to Kenyatta’s son. At the time, the election was seen as a calculated move to prepare Uhuru for bigger things. As a student of Moi and to some extent Raila, Uhuru did not disappoint.

He has come across as a fast learner after making a false start in the sub-branch party elections.

In the General Election held the same year, Uhuru contested the Gatundu parliamentary seat that was previously held by his father. He lost to Nairobi-based architect, Moses Mwihia.

After losing the election, Uhuru’s friends say that he was extremely upset and that he vowed to quit politics altogether. Wary that his adventure into politics had hit a wall, he retreated to the family business empire in the hospitality industry and commercial farming.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Up to this point, he did not know Moi was intent on propelling him to the national political scene.

The flop did not deter Moi from further propping him. He was appointed to chair the Kenya Tourism Board, where he worked closely with Nicholas Biwott, a confidant of the president, then a powerful cabinet minister.

In 2001, to pave way for Uhuru, Moi prevailed on Mark Too, a nominated MP to step down thus providing a route for Uhuru’s entry to parliament.

Even as political neophyte, Moi trusted Uhuru to the extent that he appointed him Minister for Local Government.

The handpicking of Uhuru ahead other seasoned politicians like Raila Odinga, Moody Awori, George Saitoti, Kalonzo Musyoka and many others who wanted to take part in presidential nomination infuriated the rank and file of the party resulting in a mass walkout.

The implosion was the beginning of bleeding and a slow but painful end of Kanu, as Kenyans knew it.

Despite his political inexperience at the time, Moi still believed he could propel Uhuru to become his successor, running on Kanu ticket in the 2002 polls.

And as fate would have it, Uhuru lost to Kibaki. It was from this point that Uhuru started building himself as his own man.

As leader of official opposition in parliament, Uhuru was overly critical of the Kibaki Government but at some point he toned down and joined ranks with his former adversary.

Today Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta is on the cusp of becoming the fourth President of the Republic of Kenya, but ironically he finds himself too near and yet too far, thanks to the ‘small’ matter of ICC.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.