The Ruthless Global Battle for Your Back-to-School Shopping Dollars

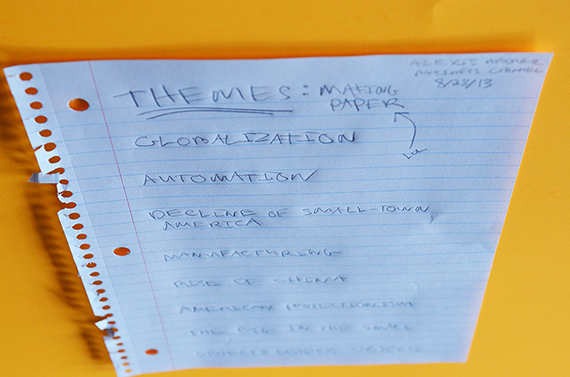

China, big box retail, and automation: the economic development of the world as seen through the iconic school notebook

In a world of cell phones and iPads, there's one back-to-school product both grandparents and children share: lined paper. Whether it's three-hole punched for a binder, perfect-bound into a black-and-white composition journal, or waiting to be torn out of a spiral notebook, lined paper is the medium of schoolwork.

While the products have remained the same, the industries that manufacture and sell paper have been buffeted by the forces of globalization, mechanization, and automation that have transformed nearly every industry.

Domestically, paper and notebook producers like Mead, Norcom, and Top Flight employ about 500 people at factories in small-town Ohio, Georgia, and Tennessee. They used to employ many, many more. In the early 1980s, a single Mead plant in St. Joseph Missouri employed more than 900 people during the peak back-to-school production season.

But very cheap imports combined with retail dynamics in the United States have produced an incredibly competitive marketplace. The school-supply paper market is as seasonal as Halloween costume rentals. And worse, the paper and notebooks are what retailers use as their loss-leader or door busters. The cheaper the notebooks that kids need, the more families come to the store and end up buying the expensive higher-margin stuff that kids want.

That makes retailers intensely price sensitive. They're already going to lose money on the notebooks, so they want to lose as little as possible. With just a few national chains — Walmart, Target, CostCo, the office supply stores, the pharmacies — controlling most of the market, they have an immense amount of bargaining power and can squeeze their suppliers, who are providing a lightly branded commodity product.

Chinese imports of school-supply paper products grew steadily through the 1990s from a little over $9 million in 1990 to $170 million in 2000. Then they doubled between 2000 and 2005 to $344 million, according International Trade Commission Data.

American paper companies were on the brink of disaster. They were getting beat on price, which left their factories running below capacity, which made them less efficient, which hurt their margins even more. And if they weren't spinning off cash, they couldn't invest in the sorts of machinery that could lower their per-unit costs and keep them more competitive.

It's the sort of situation that has crushed American manufacturing. And while the executives at companies swamped by foreign competition might find new jobs in new industries, it's a lot harder for the workers, especially ones who've built their lives in the small towns where their jobs were located. Finding another job in Philadelphia is tough enough. But try the manufacturing job market in Griffin, Georgia, population 23, 628, where Norcom has a facility.

Things got so bad, in fact, that the American school supply companies and the union representing their employees went to the U.S. International Trade Commission in 2006 to ask for "anti-dumping" action against China, India, and Indonesia. They claimed paper suppliers from those countries were subsidized by their national governments, and thereby were able to sell their products below "fair value." Furthermore, they were selling paper cheaper in the US than they were at home, crushing the American industry. And the ITC eventually did level steep levies, essentially, particularly against Chinese paper products, an action they renewed for another five years in 2012.

But what's really fascinating is that the hearings the ITC conducted to determine what actions to take provided a peek into an industry pushed to the edge of extinction.

Top Flight Paper CEO George Robinson proved an eloquent advocate for his company and industry. The outfit is located in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where its factory employs 150 people, some of them for decades. It's a family-run business, too: CEO George is the grandson of one of the men who founded the company in 1920, H.T. Robinson.

"I've been working at the company since I was 15 years old. Today, I work with my father, my uncle and three of my first cousins, as well as over 150 Chattanooga area residents," he told the ITC last year.

And yet, it didn't seem like they were going to have much of a choice back a few years ago.

That's left unions in a weaker bargaining position, struggling to support workers while helping the companies stay in business. They've given ground in hopes of keeping the manufacturing jobs in the US.

"There's been changes to work rules and other items so that the company can bring machines in, move machines around in order for the company to remain competitive," LeeAnn Foster, the union representative at the ITC hearing said. "I want to emphasize that both of these facilities and I believe the other producers that are in, their facilities are in rural areas. These are family supporting jobs in rural areas where the communities very much rely on these jobs. We've gone to the mat for the employers to be able to compete and to survive, but we're only able to do that and that's only possible if the unfairly traded goods do not come back from these three countries. We're only able to work with an employer that is there."

Which brings us back to the question of what to do about school-supply paper imports from other countries. For the next five years, Chinese and Indian paper will continue to get slapped with penalties leveled by the ITC, which the American paper companies say are crucial for maintaining their health.

But what about the other side of it? I talked with Mike Shor, who represented Indonesia at the 2012 ITC hearings. He got Indonesia taken out of the ITC order. To his eye, it looks like the Chinese "get screwed." In essence, American regulators class China as a non-market economy. So when they do the calculations to see if Chinese companies are dumping their products on the US market, they won't use data from China itself, but from a purportedly analogous country like the Philippines.

Under this system, the numbers always seem to come out stacked against the Chinese. Most countries will get levies of five to twenty percent, Shor said, but "in these China cases, it's more like 50 to 200 percent."

"The dumping and subsidy calculations are done by the International Trade Administration in the Office of Commerce, an Executive Branch agency," Shor said. "Who are they more interested in protecting, the domestic industry or the Chinese?"

The answer, of course, is the domestic industry. Especially when there are Congress members like Ohio Republic Rob Portman calling on the ITC to protect Mead jobs in his district.

What adds one final wrinkle to the equation is that American paper brands like Mead do, in fact, also import and sell notebooks from other countries, most notably Mexico and Vietnam (which does not show up in the chart above, but is the dominant foreign supplier of composition books).

So what you're holding in your hands when you've got an unbranded composition book, made in China, or a Mead college notebook from an Ivy League bookstore, or a spiral-bound Top Flight from CostCo, is the simple end product of an incredibly complex system. The state of the world is in that notebook, even before you fill its pages: The two most powerful nations in the world supporting their domestic industries. Small-town America on the brink of collapse. Automation making some American workers obsolete, while foreign competition eliminates the positions of most of the rest.

And at the center of it all, ruthless competition for the back-to-school shopper's presence and therefore dollars: the battleground is blue-lined paper, and the war is won with a few nickels of price differentiation.