A Century of Misery for Retail Employees Just Before Christmas

In the early 20th century, reformers mounted a "Shop Early" campaign to spare workers from the holiday rush. It still hasn't succeeded.

On Christmas Eve, the mall parking lot is a zoo, store clerks are harried, and the UPS man is frantically making sure that holiday parcels are delivered before deadline.

Why?

The progressive reformers of a century ago would've pinned the blame on a selfish public's failure to conscientiously complete their Christmas shopping early, so as to spare the nation's workers from the horrors of an annual holiday rush.

"Thousands of workers in every city have been taught by bitter experience to look forward to Christmas with dread," the Consumer League of New York lamented in one of its typical magazine advertisements from that era. "Every shop girl knows that the coming Christmas season will mean to her an extra amount of work, of nervous strain and exhaustion. The great army of workers whom you do not see–the bundle wrappers, drivers and errand boys–look forward to Christmas as a hateful time of undeserved effort and hardship. A very little unselfishness on your part will greatly lighten the burden of these working people. Merely do your Christmas shopping early–early in the month, and early in the day."

The daily headlines make it easy to imagine that long holiday hours are an innovation of our era. This year alone we've heard about "Black Friday" sales that began on Thanksgiving Day, Amazon.com deliveries arriving on Sunday, and Kohl's staying open 24 hours a day for the final countdown to Christmas morning.

But the holiday rush was an annual event in bygone eras too.

In 1896, when the New York State Legislature forbade stores to work women younger than 21 or boys younger than 16 for more than 10 hours per day or 60 hours per week, lawmakers exempted the days between December 15 and December 31. The consumer economy fueled intense demand for labor even then.

The organized effort to encourage consumers to "Shop Early" began in 1903, when progressive reformer Florence Kelley published her essay "The Travesty of Christmas."

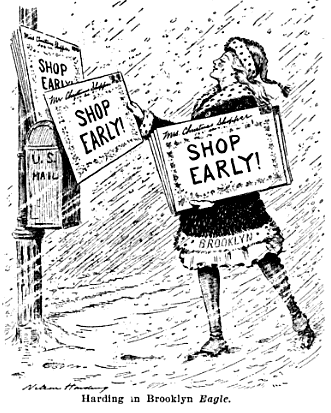

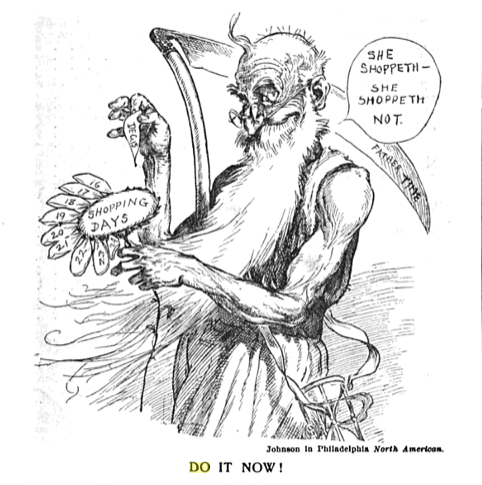

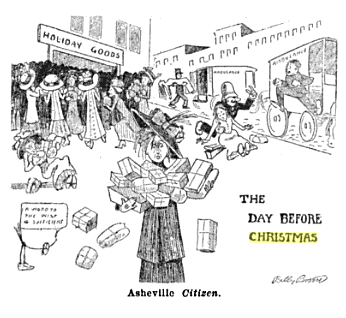

By 1905, the Consumer League of New York was publicizing the effort regionally, and the worker friendly movement soon became a nationwide phenomenon. Newspapers printed cartoons urging early shopping. Magazines ran tales of woe from working women. "One day I was not relieved at night for supper till nearly 8 P.M., after demonstrating dolls at an aisle counter all day," one salesgirl is said to have told labor investigators. "I was so exhausted that I finally broke down and cried from fatigue. The millinery buyer came and asked me what was the matter, and I told him. I said I had not sat down all day, and if I could only go off the floor a few minutes I could rest, and that would stop my crying."

In addition to urging consumers to change their shopping behavior, various consumer leagues encouraged businesses to restrict their hours during the holidays.

The Survey, a magazine dedicated to social welfare, touted one success story in 1911: "Larger merchants in Philadelphia agree to close at 6 pm throughout the holiday shopping season." The campaign persisted too, as evidenced by my favorite "Shop Early" tract, from a 1918 issue of the Civic Club Bulletin of Philadelphia (emphasis added):

The Consumers' League again, but with more zeal, if possible, pleads with the purchasing public to shop early, because the usual Christmas rush this year will mean ever so much more work for a very limited number of employees in a very limited number of hours. This almost always means fatigue and a consequent lowering of the workers' vitality, and therefore more or less sickness following. The fact that we are asking you to give your serious consideration to this matter through the following limerick (which appears on our Christmas card) does not mean we wish it treated lightly. The underlying truths are carrying our thoughts and pleadings.

The Government says to you, Why

Can't you exercise sense when you buy?

To shop when you oughtn't

Is just as important

A sin as to hord, steal and lie.SHOP EARLY! We need our girls' vim;

We can't replace her by a him.

Don't go and exhaust her,

And make Christmas cost her

The joy that the season should bring.– A Estelle Lauder, Executive Secretary

As another critic of the holiday rush complained, the long hours left employees spent by Christmas Day, which too many salesgirls spent away from family, exhausted in bed. Little wonder that late shoppers were sometimes vilified by campaigners. Core to "Shop Early" was the notion that "the crowding of the shops by late purchasers of Christmas gifts is a crude and obvious denial of the Christmas spirit," as a 1913 editorial in the The Outlook magazine put it. "It is dishonoring the day to cause thousands upon thousands of girls and women to dread its approach."

The "Shop Early" ethos was around for decades, though it faded along with the political star of the progressives who popularized it. Today, some people still try to shop early, but the ethos is dead. Every opportunity for consumer convenience is extolled.

"Behind on your holiday shopping?" Gizmodo wrote just yesterday. "No worries. Amazon's got free overnight shipping on thousands of products through tomorrow. Here's the best of what can still get to you—for free—in time for Christmas morning. Everything below ordered by tonight (12/23) at 11:59 PM EST will get to your house by end of day Tuesday, with plenty of wrapping time to spare."

Of course, other relevant factors have changed.

A century ago, one horror story invoked by the "Shop Early" movement concerned a child delivery boy who worked for 19 hours delivering packages in the New York City winter, felt too exhausted after his shift to go home, fell asleep while resting in the wagon where the goods he delivered were kept, and died of exposure. UPS and Fed-Ex employ grown men now. None are likely to freeze this Christmas

Indeed, there are all sorts of reasons that "Shop Early" would be unlikely to take hold today. Our society is more diverse and less religious, making for more workers who don't mind Christmas work. The rush is a boon to seasonal workers making a bit of money after a long period of unemployment; early shopping is now associated with Black Friday excesses–stores opening on Thanksgiving itself, consumers fighting over big screen televisions–more than conscientious attempts to spare workers; and with some exceptions, the holiday workforce of 2013 enjoys much better labor protection than than laborers of the '10s, '20s and '30s.

Still, if you've been on an airplane or at a department store cash register in the last few days, it's apparent that the workers staffing the Christmas rush are forced to suffer daily at the hands of stressed, often impolite, occasionally abusive consumers, almost all of whom are enabled by a business culture that flatters customers with the conceit that they're always right, even when they're jerks. Shop Early may be dead, perhaps for the best. But the need to be cognizant that too frequently mistreated people are running shops and delivering packages still exists.

So be nice to the harried clerk ringing up your purchase, even if he is off his game or she is distracted by other customers. And think about tipping the UPS delivery person for once. If someone is helping you on Christmas Eve this year, odds are they're more stressed than any of the people they're ringing up, checking out, or otherwise helping with goods or services.