A dog is drowning in quicksand. Its grey head pokes defiantly out of the brown sludge, even as a dead yellow sky above insists there is no hope. No saviour. In the next painting, supernatural shapers of the world reveal themselves, but they are grinning hags floating eerily above a lifeless landscape in the dead of night – the Fates, arbitrary and uncaring. Over on the other side of the gallery is a paternal god, of sorts, but it is the ancient deity Saturn and he is eating one of his own children, as if chomping on churros at a Spanish bar, with blood instead of chocolate sauce.

These are Francisco Goya’s Black Paintings, which hang today in their own room in the Prado museum in Madrid. Goya painted them as murals for a house he bought in 1819 when he was in his 70s. They are paintings unlike any others. Bereft of belief, bereft of optimism, they dwell on desolate images in a palette robbed of light. These bizarre scenes – imagined by Goya in the twilight of his life (he was born in 1746 and died in 1828) – have terrible resonance in the modern world. But how did an artist who grew up in the age of powdered wigs create some of the most disturbing – as well as earliest – masterpieces of modern art?

The simplistic answer, found in biographies of Goya, is that he went deaf as a result of illness in 1792, and after this his vision darkened. His early work, so the story goes, is bright, joyous and sociable. He became famous for designing tapestry scenes of everyday fun for the Spanish court, and for painting the characterful portraits about to go on show at the National Gallery in London. Then deafness struck and this happy Mozart turned into a surly Beethoven.

I don’t buy it. Not many people deal with deafness by filling their house with morbid murals. Could there be another explanation for Goya’s astonishing one-man artistic revolution? My quest to find why Goya became the darkest of all artists led me to follow in his footsteps, starting with a pilgrimage to the Principe Pio hill in Madrid. Here, on the night of 3 May 1808, Napoleon’s soldiers executed those who had participated in the previous day’s rebellion against the French occupation of their city.

An Egyptian temple, relocated when the Aswan dam was built in the 1960s, now stands sepulchrally on the hilltop. In its deathly chambers, the ghosts of the murdered might linger. Their greatest monument, however, is in the Prado. Goya painted The Third of May 1808 for the Spanish king in 1814. This public painting is just as shocking as his own private “Black” paintings. In the nocturnal glare of a lantern, a man spreads his arms as if being crucified, looking out of huge eyes at a hunched row of faceless French riflemen. A monk clasps his hands; other people queuing up for death cover their faces or look up defiantly. More acutely perhaps than any other work of art, this painting makes you feel what it must be like to know you are going to die in the next few seconds. A monstrous, unforgettable pool of blood slimes the earth.

The work is one of Madrid’s icons, yet to understand the feelings in it you have to look further than that quiet hill where a bloodbath took place. The true horror of Goya’s experience of war can best be understood by taking a train to Zaragoza, in north east Spain, the city where he grew up and trained as a painter. In its Cathedral-Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar, you get an overpowering sense of the religious, archaic Spain he would have been immersed in. Frescoes by the young Goya decorate its dusty vaults, but people do not look up at them. Instead, one by one, the devout enter a coral-coloured alcove to kiss a stone pillar on which the Virgin Mary is said to have once appeared, flanked by angels. The Virgin of the Pillar made Zaragoza a great centre of pilgrimage in Goya’s day, and Catholics venerate her still.

Goya’s own feelings about the Virgin of the Pillar can, I think, be guessed from his late works. There is no trace of Christian faith in his Black Paintings. They constitute, especially when you compare them with the religious paintings he was trained to do in this city, a vicious act of sacrilege: a vision of a world without the Christian God. Yet Goya never forgot Zaragoza: it was to return to the centre of his imagination in a terrible way.

Goya started to get work in Madrid in the mid-1770s when he was about 30; by the 1790s, he was rich and famous. As painter to the king, he was so good at his job that he could get away with portraying the royal family as a bunch of ill-favoured idiots in his masterpiece of irony The Family of Charles IV. But already his world was falling apart – and not just because he was deaf.

It was said the real ruler of Spain at the time was Manuel Godoy, the prime minister, who everyone believed to be the queen’s lover. Godoy was good-looking and knew it: in Madrid, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando has many portraits of him, including a fleshy, melancholy one by Goya. While everyone outside the court loathed Godoy, the king and queen reserved their hatred for the crown prince Ferdinand, who hated them back.

Napoleon pretended to support Ferdinand in an attempt to seize the throne and overthrow the reviled Godoy. Instead, once he got the prince in his clutches, the French emperor set out to install his own brother Joseph as ruler. But Napoleon hadn’t reckoned on Spanish pride. The rebellion against the French in Madrid in May 1808 was the beginning of a war that Napoleon could not win. All over Spain, guerrilla forces and maverick generals started pockets of resistance, later to be supported by the British general Wellington.

The most heroic of all was the revolt of Zaragoza. General Palafox took command of Goya’s home city and fortified it. As the French attacked, a popular resistance held them back at huge human cost. This battle seized Goya’s imagination. How could it not? He had lived much of his life in Zaragoza and still had friends there.

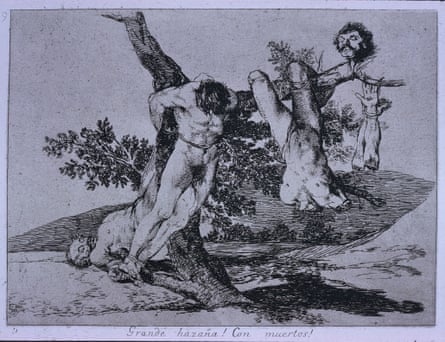

His most moving depiction of the siege shows a young woman standing among the bodies of her dead comrades, firing a cannon. “What courage!” exclaims the caption. The image, from a series called The Disasters of War, shows a real scene: Agustina Zaragoza Domenech (also known as Agustina of Aragon) was a young Catalan woman who singlehandedly took over a cannon when its gunner was killed. However, Goya’s close experience of the war brought only disillusionment. Courage is much less visible than cruelty in The Disasters of War: Zaragoza, after all, could only hold out for so long. He remorselessly shows the atrocities committed by both sides. Because this was the first guerrilla war, it released a new kind of violence. In one scene, a man simply vomits at what he sees. Goya’s repeated scenes of rape, torture and mutilation induce that same nausea. It is hard to look at The Disasters of War for long.

In Zaragoza today, the violent past of Spain seems remote. On a blazing afternoon people pass the time in cool cafes. A bomb from the Spanish civil war of the 1930s, preserved in the cathedral, looks like a harmless relic – even that conflict is far off now. Visiting the city’s small museum dedicated to Goya, I study his prints, marvelling at his imagination. On the way out I buy a book of them, the cannon-firing girl on its cover. Turning the pages, I am again beset by horrors nothing can explain.

Surely it was the madness of this war, not deafness, that drove Goya into the darkest regions of his mind. Here in Zaragoza – where people fought French soldiers in the narrow streets, and where as a young painter he churned out consoling religious nonsense about miracles and holy pillars – Goya looked into hell. And the Black Paintings are what he saw.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion