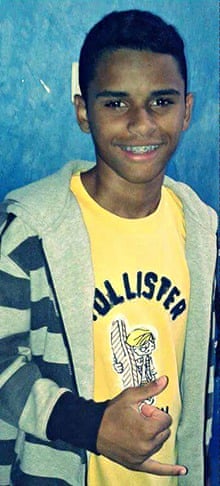

A black teenager gunned down by police. A grieving family. A furious community. And then, after a few days of tears and anger, a story that fades from view, leaving only the private misery of a heartbroken mother and a bereaved brother searching for justice.

The shooting of 15-year-old Lucas Lima in Rio de Janeiro bears similarities with the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. But the response of the public and the authorities could hardly be more different.

While Brown's death at the hands of police in the US sparked violent protests, international condemnation and a nationwide debate about racism and violence - few people outside the Alemão favela in Rio de Janeiro will have heard of Lima.

The killing of the 15-year-old has made barely a ripple in Brazil's public consciousness, in part because it is all too common. Although Brazil has a population that is a third smaller than that of the US, it has almost five times as many killings by police. And though the vast majority of the victims are black or mixed race, there is far less of a debate about race.

Lima was killed on 22 June on his way home from a football game with his friends. It was not yet dark, but his was an extremely violent neighbourhood. Dozens of residents and five police officers had been killed in Alemão - a bastion of the Comando Vermelho drug trafficking organisation - and the nearby Penha favela in the first seven months of the year. One of those officers was shot hours earlier, making police more jumpy and trigger-happy than usual.

According to his brother Tiago, Lima was coming down one of the favela's many steep roads, when he encountered police who were chasing after a group of local youths. Seconds later, he was lying lifeless on the street, along with another young victim. Police reported finding a gun between them. Who it belonged to is unclear. Tiago believes it was put there by police to cover up their mistake.

"This happens all the time. Every day, there are shootings and killings by police," said Tiago. "Almost all of those who are killed are mixed-race young men from the favelas. The police are ill-prepared. They don't come here thinking there are good people here as well as criminals. They just want to do a job and, excuse my language, fuck everyone else."

The local community protested briefly, but compared to Ferguson, the reaction was muted. While Brown's death in the US prompted criticism of police racism and a militarised law enforcement apparatus that has killed more Americans in the past decade than the war in Iraq, the death of Lima was only briefly covered in the Brazilian media. Even in his neighbourhood, many felt powerless to do anything.

"There are many injustices, but we are too afraid of the police to stand up to them. That's why nothing changes. Even if you complain, nobody listens. It's too common. People just think 'oh, another death'," said Tiago. "My brother is just a statistic."

Based on official data, academics and NGOs estimate that about 2,000 people die at the hands - or guns - of law enforcement officers in Brazil each year. The comparative figure in the US is about 400. In 2013, the number in the UK and Japan was zero.

"Ferguson is a daily occurrence in Brazil", noted Ignacio Cano, of Rio de Janeiro State University, whose studies have shown that blacks in Rio are three times more likely to be wounded or killed by police than would be expected by their share in the population.

This may be a conservative estimate. Cano said the problem is grossly under-reported by the authorities."The Brazilian state doesn't take these police shootings seriously. If it did, we'd have good data on it."

Fransérgio Goulart, a black activist who recently produced a map of killings in Rio, said his research showed that homicides among whites fell in the past 10 years, while the rate increased in the black and mixed-race population.

"We have numbers that equate to a war," Goulart said. "The central issue in these homicides is institutional racism," he said. "The war on drugs is, in reality, a war on poor and black people … The state is killing young, black males."

Goulart helped to organise a recent demonstration "against the genocide of black people" – but it attracted nothing like the same level of participants or media attention as the protests in Ferguson. Last Friday, rallies took place in 18 cities, but the biggest drew less than 400 in Rio and 1,000 in São Paulo.

Police spokesmen say the high number of shootings by police reflects the violence of a society in which more people are murdered than any other country in the world and where officers often die in the line of duty. They also note major improvements in some cities. In Rio, which has the most killings by officers, there are now about a third of the cases of a decade ago. Most are classified as having taken place when the victims were "resisting arrest". Video evidence often disproves this.

In June, a dash-cam on a police car caught police officers chatting about "hitting the target" after two teenagers who had been in their custody were left dead on the road. "Two less," one says. "If we did this every week, it could start declining."

In March, passersby filmed a police car dragging a woman along a street after the officers had injured her in a shootout and thrown her in the boot. Mother-of-four Claudia da Silva Ferreira died soon afterwards in hospital.

Protests are usually localised, short-term and make little impact. In May, residents in Manguinhos took to the streets after a 19-year-old Jonathan de Oliveira Lima, was shot in the back by police. In April, demonstrators erected blazing barricades in Copacabana after the body of dancer Rafael da Silva Pereira, was found in a school during a police operation in the Pavão-Pavãozinho favela.

While the killings far outnumber those in the US, the reaction of a white-dominated media has - for the most part - been more resigned than angry.

"If every death of a young black man by police in Brazil prompted segments of the population to fill the streets as in Ferguson, we would live in a state of daily seizures," opined columnist Luiz Fernando Vianna in a Folha do São Paulo article headlined, "Ferguson is here."

Additional reporting by Anna Kaiser