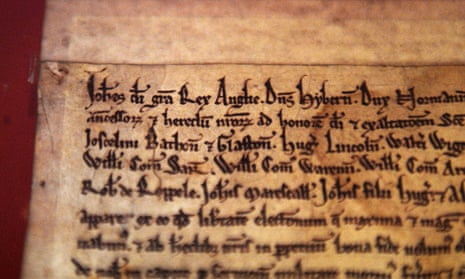

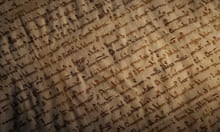

Lawyers, scholars and citizens will gather on Monday night at the British Library to examine the iconic power of a wrinkled piece of parchment, covered with faded, semi-legible medieval script, now 800 years old. We like to think Magna Carta has this power because it represents the beginning of what we hold in common. It may be iconic for the opposite reason: because it frames fundamental disagreements and forces us to understand just how far back these disagreements run.

Its key clauses lay out the lineaments of the rule of law, but this principle divides us, because the question remains: whose law? This argument is at the heart of modern British politics. On one side, mostly, but not exclusively, conservative, are those who think Magna Carta inaugurated a tradition of freedom that is distinctively British, or should I say, English, since it is unclear if the Scots and Welsh feel their liberties flow from the same source.

From Magna Carta originates the English common law, a tradition built upon empirical precedent, distinct from European civil law based on abstract principal. For conservative opinion in England, rule of law means law made by the English people, through common law and statutes. Together, common law and parliamentary sovereignty add up to what conservatives mean by democracy.

On the other side, there are the liberal and progressive traditionalists who think that their inheritance of freedom has never been insular. England shared the Magna Carta tradition with Europe and, in return, English radicals in 1640, 1688 and 1792 borrowed from European natural rights tradition. Since the 1990s, this progressive and liberal tradition has believed that majority rule in parliament must be counter-balanced by constitutional rights and judicial review and by transnational European protection, in the form of the European Court of Human Rights.

David Cameron recently used the Magna Carta commemoration to announce that his government will introduce a bill to limit the rights of British citizens to appeal to the European Court. It’s not clear if he will eliminate citizens’ rights altogether, if he will take Britain out of the court, and it’s not clear that such a move is legally feasible. It may be that the prime minister has raised the issue only to toss political meat to his dogs, but that he feels he has to feed them is significant.

The political impulse – to restore a rule of law that is English – speaks to deep feeling in the conservative opinion. The liberal opposition to Cameron’s proposal speaks to equally deep feelings about the need to balance parliamentary sovereignty with a rule of law anchored in Europe and safe from the tyranny of passing majorities.

In thinking about this argument, it is best to steer as clear of ideology as we can. The law can be an ass, whether it is seated in Strasbourg or Westminster and parliaments can make fools of themselves as surely as judges can.

There aren’t any fail-safe guarantees of freedom: not in judicial review, constitutional rights, international human rights, majority rule or national sovereignty. Each of these supposed bulwarks can be breached, so the best a citizen can hope for is for competitive institutions, each checking the other and preventing oppression or foolishness. This argument, in favour of as many defences of liberty as possible, supports the claim that it would be unwise for Britain to legislate limitations on a citizen’s rights to go to the European Court for redress. Of course its judges will make decisions – giving prisoners’ rights to vote or protecting the rights of accused terrorists – that will infuriate British majorities but that is what any self-respecting human rights court is supposed to do.

A European-wide rule of law, backed by a transnational court, has done as much as the Marshall Plan and decades of prosperity to anchor democracy in Europe. Conservatives used to understand this. Clement Attlee sent his attorney-general to help draft the European Convention on Human Rights because he understood that Germany, France and Italy might stray from the democratic camp unless there was a court to protect the liberty of their citizens. This is the larger vision of Britain’s place in Europe – and Magna Carta’s immense contribution to European freedom – that Downing Street is in danger of forgetting.

Michael Ignatieff teaches at the Harvard Kennedy School. The Power of Iconic Documents event is at the British Library, London, tomorrow