I think that folks who follow me on Twitter will have worked out by now that I plan to vote Remain in the EU Referendum, and furthermore think that calling the whole thing in the first place was something of an economic own goal. The consequences appear to me extremely likely to be economically and financially negative for the country, which is why Remain are so keen to focus on the economics and Leave are so keen to move the debate on to anything but.

Despite news media saturated with coverage, I listened today to an old podcast (16th March) of Radio 4’s excellent Moral Maze that discussed the morality of Brexit, during which Michael Portillo put the moral case for Brexit as ‘What Price Liberty?’. (He actually asked an American whether there was a price at which Americans would give up independence, but it comes to the same thing.) This is both a really good way to argue for Brexit, and also a really good general question. It asks you to look deep into yourself and decide whether you are sufficiently mercenary as to put your freedom up for sale. Posing this question as a Brexiteer puts you on the side of principle, and I have no doubt that many if not most on the Leave side see themselves as freedom-fighters even if I don’t see them as anything of the sort.

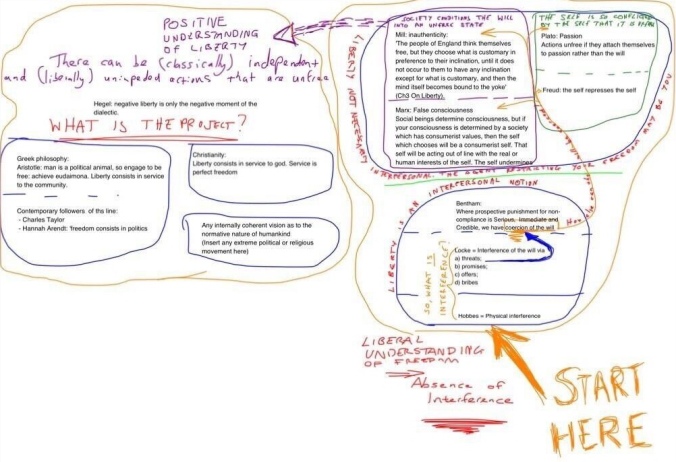

It is also a wonderful question because it asks us to think about what liberty actually means to each of us. Sounds pretty basic, no? Freedom is the ability to do what you want to do, right? Perhaps, but this is a question with which I have struggled since an undergraduate, despite being lucky enough to attend a lecture course by the awesome Quentin Skinner on the subject and having read many of the texts to which he refers. A couple of years ago I downloaded Skinner’s iTunesU lecture ‘What is Freedom’ which seems like a potted version of the whole course and drew from it the following diagram:

Starting at the bottom right, we begin with Hobbes, for whom freedom is lack of physical interference. To Hobbes, the Highwayman’s question ‘your money or your life?’ was fair – you were free to choose and as such could never be made unfree in the experience of being robbed (or indeed tortured into confessions etc). Locke then comes along and asked how interference might be extended beyond the physical, and with Bentham we have a more formulated version as to how the will (rather than just the body) might be coerced. At this point liberty is still an interpersonal notion. As we move to the top right bubble we then progress to the idea used by Mill and Marx: that liberty is not necessarily interpersonal and that the agent restricting the self may actually be you (through false consciousness or Mill’s idea of inauthenticity). These echo ideas advanced by Plato, and – away from tracts on liberty – were also worked on by folks like Freud. All this so far describes only what is known as ‘negative liberty’ – aka freedom to do what you want to do – and not its ‘positive’ moment (where freedom consists in essentially fulfilling your mission, however described), outlined on the left hand side of the diagram.

What is absent from this diagram is Skinner’s rather fascinating third leg of liberty, which comes from neo-Roman understandings of freedom that are based on absence of dependence (eg, you are subject to the arbitrary will of another agent), rather than on any absence of interference. It’s not that you can’t do what you want to do, but rather you know that another agent has the power to arbitrarily interfere if it so sees fit, and as such you self-censor. This neo-Roman understanding of liberty can be deployed extremely powerfully against monarchy, colonialism, gender inequality, and the modern day state’s interception of electronic communication. I may well have misunderstood, but as far as I can tell it is also the most powerful argument in the Brexiteer’s intellectual arsenal.

What can be said against such a noble argument? Plenty of things, although some are conditional on different understandings of liberty. Folks who appeal to the UK’s EU membership enabling the UK to better collectively combat climate change, international terrorism etc are sort of relying upon an understanding of a collective shared project – kind of leaning on a positive concept of liberty. I can see why this doesn’t wash with them. And folks who talk about economic impact of Leave are perceived to be speaking a utilitarian dialect that is equally impenetrable to intellectual fans of Leave.

Speaking in neo-Roman terms then, our power to hold the Brexit Referendum proves the lack of dependence. The power to leave existed before the government decided to call the Referendum. The power to leave is precisely what undermines the intellectual underpinnings of the Leave campaign. If we wish to examine whether to exercise this power we should look at the costs of so doing. And the welfare costs of so doing seem great.

I view the current referendum as an hilarious parody of the Scottish referendum in 2014. The people now going on about ‘sovereignty’ are middle class English people who couldn’t be further, socially and politically, from Scottish independence supporters. Exactly the same mantras are made to any well argued reason for staying in the union: ‘Project Fear!’, ‘scaremongering!’. I have no problem with someone wanting out of the EU (or the UK) just so long as they haven’t wilfully blinded themselves to the potential problems.

LikeLike