How Jews Designed the Modern American Home

The mid-century modernists who fled Hitler helped shape a visual aesthetic that's still pervasive, as shown in a new museum exhibit.

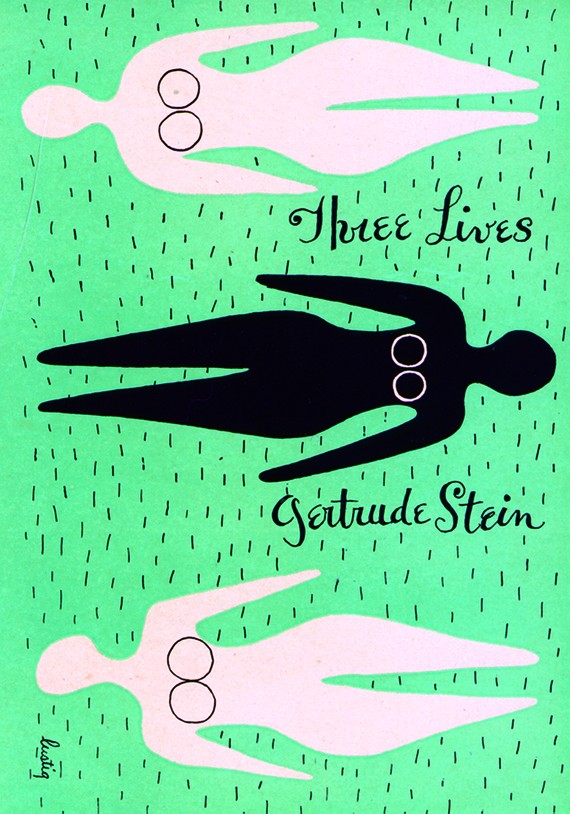

Not every American mid-century modern designer was Jewish. But an awful lot of them were. Immigrant and second-generation Jews like George Nelson, Alvin Lustig, Anni Albers, Saul Bass, Paul Rand, Richard Neutra, Leo Lionni, and others helped shape the epoch-defining, less-is-more, Bauhaus-inspired aesthetic that was a pervasive presence in many American homes and businesses during the postwar period.

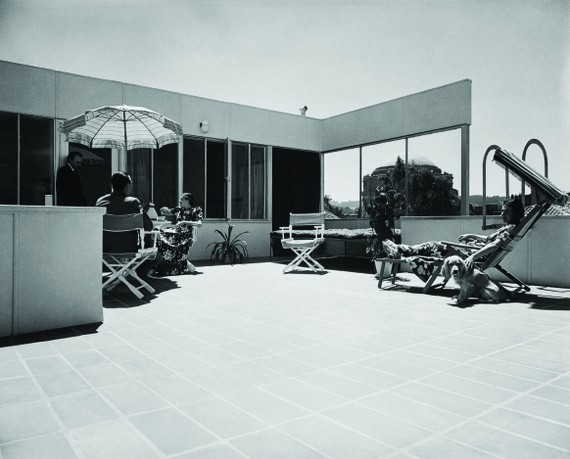

Designing Home: Jews and Midcentury Modernism, an exhibition on view at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco until October 2014, looks at how key Jewish designers—including graphic, product, and industrial designers, plus architects, patrons, and merchants—helped forge a distinctly American look that continues to exert a profound influence on contemporary style.

It was Hitler’s war on “degenerate” modernism that triggered Jewish architects and designers to take refuge in the U.S. “An informal network of six non-sectarian organizations” helped promote their works once they got here, writes Designing Home’s guest curator, Donald Albrecht, in an email. That network included institutions like Black Mountain College, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis, and the Bay Area at Pond Farm in Guerneville, which hired Jewish architects and designers as faculty members or promoted their work in museum exhibitions and publications (like the California-based Arts & Architecture).

“One of the reasons I wanted to discuss the networks was to tell a story of Jewish assimilation into the mainstream of design via collaboration,” Albrecht says. He wanted to avoid a more shallow reaction—a mere, “WOW! I didn't know [fill in the blank] was Jewish.”

In Designing Home, the concept of “home” is addressed broadly. Furniture, textiles, magazine graphics, and architecture are used to represent designers from all over, whose works ranged from precious and ubiquitous. For instance, there is a one unique Anni Albers wall sculpture next to the popular Henry Dreyfuss Honeywell thermostat found in virtually every American home.

Jews had previously been excluded from the architecture and design fields as principals, but the period showcased in the exhibit marked something of a turning point. “I don't know if modernism triggered the change, [but it caused] a lessening anti-Semitism after WWII,” Albrecht says.

But prejudice, and the specter of exclusion, were never entirely absent. “MOMA’s promotion of the Bauhaus style was not without controversy,” Albrecht writes in his catalog essay, “Avant Garde Neither Gentile Nor Jew,” about an earlier landmark Bauhaus exhibition:

Shortly after Bauhaus 1919–1928 opened, the museum’s director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., wrote in a letter to Gropius, who supervised the Bauhaus exhibition and book, “As we could have guessed, we have already heard reports that the exhibition is considered ‘Jewish.’ Many Americans are so ignorant of European names that they conclude that, because the Nazi Government has been against the Bauhaus, the names Gropius, Bayer, Moholy-Nagy, etc., are probably ‘Jewish-Communist.’” Barr wanted to squelch criticism by proposing inclusion of this statement:

“... It should be stated that, although the Bauhaus welcomed Jewish students, there were no Jews on its faculty (or there were only two Jews out of fourteen on its faculty, or whatever the proportion was).”

Gropius’s response to the exhibition’s organizer and designer, Herbert Bayer (quoted by Albrecht): “I refused to permit that, strictly, because I don’t want to get into any discussions on that subject—despite the fact that we have only one Jew among our whole faculty.”

Despite its growing acceptance among middle- and upper-class Americans and corporations, modernism was not an entirely uncontroversial aesthetic. Accused of being “Bolshevik” by the Nazis, in America its practitioners were tainted at times as leftwing. Still, Albrecht found that Jews had a large impact, “which I can't quantify, but do think encompassed a greater percentage of modern architects and designers than the percentage of Jews in the US.”

For Jews themselves, an interest in Modernism was in some cases intertwined with Jewish customs. “Many Jews were here to stay,” Albrecht explains, “so they worked to make a good home in the U.S. and, for some, that good home meant good modern design, especially in new suburbs.”

So Jewish entrepreneurs in America promoted the avant-garde for reasons both fraternal and opportunistic. “It was, perhaps, a way to be free of a sometimes painful past,” Albrecht says. Yet, he adds, Jews also embraced Colonial Revival. “Both perhaps were ways to enter the mainstream—one via ‘America the new,’ the other via America history.”