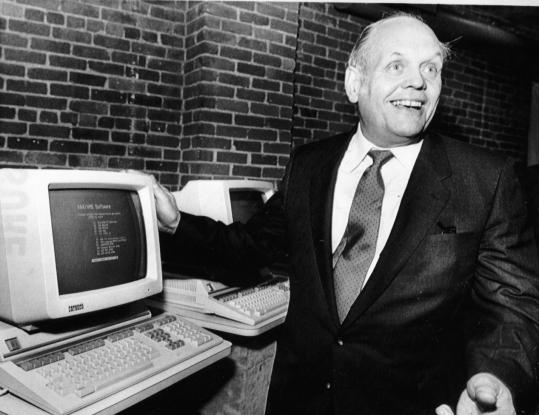

Ken Olsen introduces equipment in the the Microvax ll computer system in 1985.

(File 1985/Associated Press)

Ken Olsen introduces equipment in the the Microvax ll computer system in 1985.

(File 1985/Associated Press)

The innovator

Ken Olsen changed the course of computing history

Ken Olsen introduces equipment in the the Microvax ll computer system in 1985.

(File 1985/Associated Press)

Ken Olsen introduces equipment in the the Microvax ll computer system in 1985.

(File 1985/Associated Press)

IN 1987, Ken Olsen stood before 3,000 Digital Equipment Corporation employees and their guests at a gala kickoff dinner for DECworld, the company’s lavish promotional exposition at Boston’s World Trade Center. When Olsen, Digital’s legendary founder and president, had stepped to the podium to say a few words, the crowd rose to its feet and cheered for a full 10 minutes. Socially awkward, the MIT-trained engineer and entrepreneur could only stand and grin in embarrassment. After 30 years at the helm of Digital, which he founded with $70,000 in venture capital, Olsen had reached the top.

Digital was the hottest company in the fast-growing computer industry. Olsen’s renowned management style would become business school case study fodder and influence a generation of high-tech organizations. With $11.4 billion in skyrocketing sales and 120,000 employees in 95 countries, it had a market value of $24 billion and was the 13th most profitable company in the Fortune 500.

DEC was also the largest corporate employer in both Massachusetts and New Hampshire, and its million-square-foot headquarters in an old woolen mill in Maynard was aflame with excitement. Locally, DEC was far more than a company; it was a giant family with such girth and influence that it formed the economic underpinning of many communities surrounding Boston. DEC was the engine that drove the so-called Massachusetts Miracle and was the cornerstone of the Route 128 high-tech belt that rivaled California’s Silicon Valley.

Ken Olsen, who died at age 84 last Sunday, was among those rare entrepreneurs, like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, who managed to not just found but lead their companies to unparalleled success over several decades. Sadly, Olsen’s fortunes at Digital began to decline not too many years after that DECworld gala. In 1992, Olsen was forced out of Digital; in 1998 Digital was acquired by

Olsen’s stubborn disdain for the personal computer and his inability to accept the advent of open, non-proprietary systems, are well-known triggers for the company’s demise. His autocratic unwillingness to have a second-in-command or prepare a successor was a serious failing. Olsen himself unwittingly described his own fate when, in the 1980s, he said, “Success is probably the worst problem for an entrepreneur. As people get to be successful, they tend to stop learning.’’

But the outpouring of respect and affection for Olsen that coursed around the Internet after his death illuminates the man’s enduring legacy. Yes, the ultimate entrepreneur ultimately failed, but along the way, he built something unique and wildly successful.

In building DEC into a vibrant, thriving workplace, Olsen created a much-admired case study in organizational dynamics. Before there was

There was no “no’’ at DEC. Every idea could be heard and if an individual could muster the consensus of the key stakeholders, he or she could run with it. Olsen, ever the curious scientist and engineer, could often be found sitting in shirtsleeves among a group of engineers tearing apart a rival’s product in search of a better, more elegant solution.

Digital created the vast minicomputer industry which produced numerous competitors and hundreds of thousands of local jobs. DEC ruled this roost for three decades because Olsen demanded the highest quality products, the deepest respect for customers, and a simple tenet from everyone inside DEC: Do the right thing. In building an inexorable bridge between the glass-enclosed castles of the mainframe era to the interactive desktop revolution, Ken Olsen changed the course of computing history.

Glenn Rifkin is a business journalist based in Acton and co-author, with George Harrar, of “The Ultimate Entrepreneur: The Story of Ken Olsen and Digital Equipment Corporation.’’ ![]()