Peter Thiel’s CS183: Startup - Class 12 Notes Essay

Here is an essay version of my class notes from Class 10 of CS183: Startup. Errors and omissions are mine.

Reid Hoffman, co-founder of LinkedIn and Partner at Greylock Partners, joined this class as a guest speaker. Credit for good stuff goes to him and Peter. I have tried to be accurate. But note that this is not a transcript of the conversation.

Class 12 Notes Essay—War and Peace

I. War Without

For better or for worse, we are all very well acquainted with war. The U.S. has been fighting the War on Terror for over a decade. We’ve had less literal wars on cancer, poverty and drugs.

But most of us don’t spend much time thinking about why war happens. When is it justified? When is it not? It’s important to get a handle on these questions in various contexts because the answers often map over to the startup context as well. The underlying question is a constant: how can we tilt away from destructive activity and towards things that are beneficial and productive?

A. Theater

It often starts as theater. People threaten each other. Governments point missiles at each other. Nations become obsessed with copying one another. We end up with things like the space race. There was underlying geopolitical tension when Fischer faced off with Spassky in the Match of the Century in 1972. Then there was the Miracle on Ice where the U.S. hockey team defeated the Soviets in 1980. These were thrilling and intense events. But they were theater. Theater never seems all that dangerous at first. It seems cool. In a sense, the entire Cold War was essentially theater—instead of fighting and battles, there was just an incredible state of tension, rivalry, and competition.

There are ways in which competition and war are powerfully motivational. The space race was incredibly intense. People worked extremely hard because they were competing against Russians on other side. Things get so intense that it becomes quite awkward when the rivalry ends. The space race ended in 1975 with the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, where the U.S. and Soviet Union ran a joint space flight. No one was quite sure how it would play out. Was everyone just going to become friends all of a sudden?

So war can be a very powerful, motivational force. It pushes people to try and improve themselves. It’s like wimpy kid who orders a Charles Atlas strength-training book, bulks up, and pummels the bully that’s been tormenting him.

B. Psychology

But the Charles Atlas example illustrates more than just the motivational aspect of war. When people are myopically focused on fighting, they lose sight of everything else. They begin to look very much like their enemy. The skinny kid bulks up. He becomes the bully, which of course is exactly what he had always hated. A working theory is thus that you must choose your enemies well, since you’ll soon become just like them.

This is the psychological counterpoint to the economic discussion we had in classes three and four. In world of perfect competition, no one makes any profit. Economic profits are competed away. But the economic version is just a snapshot. It illustrates the problem, but doesn’t explain why people still want to compete. The Kissinger line on this was that “the battles are so fierce because the stakes are so small.” People in fierce battles are fighting over scraps. But why? To understand the static snapshot, you have to look to the underlying psychology and development. It unfolds like this: conflict breaks out. People become obsessed with the people they’re fighting. As things escalate, the fighters become more and more alike. In many cases it moves beyond motivational theater and leads to all out destruction. The losers lose everything. And even the winners can lose big. It happens all the time. So we have to ask: how often is all this justified? Does it ever make sense? Can you avoid it altogether?

C. Philosophies of Conflict

There are two competing paradigms one might use to think about conflict. The first is the Karl Marx version. Conflict exists because people disagree about things. The greater the differences, the greater the conflict. The bourgeoisie fights the proletariat because they have completely different ideas and goals. This is the internal perspective on fighting; there is an absolute, categorical difference between you and your enemy. This internal narrative is always a useful propaganda tool. Good vs. evil is powerfully motivational.

The other version is Shakespeare. This could be called the external perspective on fighting; from the outside, all combatants sort of look alike. It’s clear why they’re fighting each other. Consider the opening line from Romeo and Juliet:

Two households, both alike in dignity,

Two houses. Alike. Yet they seem to hate each other. In a very dynamic process, they grow ever more similar as they fight. They lose sight of why they’re fighting to begin with. Consider Hamlet:

Exposing what is mortal and unsure

To all that fortune, death, and danger dare,

Even for an eggshell. Rightly to be great

Is not to stir without great argument,

But greatly to find quarrel in a straw

When honor’s at the stake.

To be truly great, you have to be willing to fight for reasons as thin as an eggshell. Anyone can fight for things that matter. True heroes fight for what doesn’t matter. Hamlet doesn’t quite achieve greatness; he’s too focused on the external narrative of how meaningless everything is. He never can bring himself to fight.

II. War Within

A. What’s Past is Prologue

So which perspective is right in the tech world? How much is Marx? How much is Shakespeare?

In the great majority of cases, it’s straight Shakespeare. People become obsessed with their competitors. Companies converge on similarity. They grind each other down through increased competition. And everyone loses sight of the bigger picture.

Look at the computer industry in the 1970s. It was dominated by IBM. But there were a bunch of other players, like NCR, Control Data, and Honeywell. Note that those are longer common names in computer technology. At the time, all these companies were trying to build mini computers that were competitive with IBM’s. Each offering was slightly different. But conceptually they were quite similar. As a result of their myopia, these companies completely missed the microcomputer. IBM managed to develop the microprocessor and eclipsed all its competitors in value.

The crazy ‘90s version of this was the fierce battle for the online pet store market. It was Pets.com vs. PetStore.com vs. Petopia.com vs. about 100 others. The internal narrative focused on an absolute fight to dominate online pet supplies. How could the enemy be defeated? Who could afford the best Super Bowl ads? And so on. The players totally lost sight of the external question of whether the online pet supply market was really the right space to be in. The same was true of Kozmo, Webvan, and Urban Fetch. All that mattered was winning. External questions that actually mattered—Is this war even worth fighting?—were ignored.

You can find this pattern everywhere. A particularly comic example is Oracle vs. Siebel. Oracle was a big database software company. Siebel was started by a top salesman form Oracle—so there was a dangerously imitative and competitive dynamic from the outset. Siebel tried to copy Oracle almost exactly, right down to similar office design. It sort of started as theater. But, as is often the case, it escalated. Things that start with theater quite often end pretty badly.

At one point, Oracle hatched an interesting plan of attack. Siebel had no billboard space in front of its office. So Oracle rented a huge truck and parked it in front of Siebel HQ. They put up all sorts of ads on it that made fun of Siebel in attempt lure Siebel employees away. But then Oracle acquired Siebel in 2005. Presumably they got rid of the truck at that point.

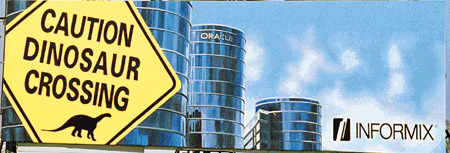

The ad wars aren’t just throwaway anecdotes. They tell us a lot about how companies were thinking about themselves and the future. In the ‘90s, a company called Informix started a Billboard war with Oracle. It put up a sign near Oracle HQ off the 101 that said: “You just passed Redwood Shores. So did we.” Another billboard featured a “Dinosaur Crossing” sign superimposed in front of the Oracle Towers.

Oracle shot back. It created a prominent ad campaign that used snails to show the TPC benchmark results of Informix’s products. Of course, ads weren’t anything new. But what was strange was that they weren’t really aimed at customers; they were aimed at each other, and each other’s employees. It was all intended to be motivational theater. Ellison’s theory was that one must always have an enemy. That enemy, of course, should not be big enough to have a chance at beating you. But it should be big enough to motivate the people who fail to realize that. The formula was theater + motivation = productivity. The flaw was that creating fake enemies for motivation often leads to real enemies that bring destruction. Informix self-destructed in 1997.

B. The End of This Day’s Business Ere It Come

The Shakespearean model holds true today. Consider the Square card reader. Square was the first company to do mobile handset credit card processing right. It did the software piece and the hardware piece, and built a brand with the iconic white square device.

Then there was a proliferation of copycat readers. PayPal launched one. They shaped it like a triangle. They basically copied the idea of a simple geometric-shaped reader. But they tried to one-up Square; 3 sides, after all, was simpler than 4.

Before PayPal’s PR people could celebrate their victory, Intuit came out with a competing card reader. It was shaped like a cylinder. Then Kudos came out with its version, which it shaped like a semicircle. Maybe someone will release a trapezoid version soon. Maybe then they’ll run out of shapes.

How will this all end? Do you really want to get involved in making a new card reader at this point? One gets a distinct sense that the companies focused on copycat readers are in a great deal of trouble. Much better to be the original card reader and stay focused on original problems, or an original company in another space entirely.

C. Even the Big Guys Do It

It’s not just startups that engage in imitative competition. The Microsoft-Google rivalry, while not completely destructive, has a lot of this Shakespearean dynamic behind it. In a way, they were destined to war with each other from day one because they are so alike. Both companies were started by nerds. The top people are obsessed with being the smartest. Bill Gates had an obsession with IQ testing. Larry and Sergey sort of took that to the next level. But Microsoft and Google also started off very differently. Originally they did very different things and had very different products. Microsoft had Office, Explorer, and the Windows operating system. Google had its search engine. What was there to fight about?

Fast-forward 12 years. It’s Microsoft’s Bing vs. Google, and Google’s Chrome vs. Internet Explorer. Microsoft Office now has Google Docs to contend with. Microsoft and Google are now direct competitors across a number of very key products. We can surmise why: each company focused on the internal narrative in which they simply had to take on the other because they couldn’t afford to cede any ground. Microsoft absolutely had to do search. Google simply had to do Docs and Chrome. But is that right? Or did they just fall prey to the imitative dynamic and become obsessed with each other?

The irony is that Apple just came along and overtook them all. Today Apple has a market cap of $531 billion. Google and Microsoft combined are worth $456 billion. But just 3 years ago, Microsoft and Google were each individually bigger than Apple. It was an incredible shift. In 2007, it was Microsoft vs. Google. But fighting is costly. And those who avoid it can often swoop in and capitalize on the peace.

D. If You Can’t Beat Them, Merge

PayPal had similar experience. Confinity released the PayPal product in late 1999. Its early competitor was Elon Musk’s X.com. The parallelism between Confinity/PayPal and X.com in late ’99 was uncanny. They were headquartered 4 blocks apart on University Avenue in Palo Alto. X.com launched a feature-for-feature matching product, right down to the identical cash bonus and referral structure. December 1999 and January 2000 were incredibly competitive, motivational months. People at PayPal were putting in 90-100 hours per week. Granted, it wasn’t clear that what they were working on actually made sense. But the focus wasn’t on objective productivity or usefulness; the focus was on beating X.com. During one of the daily updates on how to win the war, one of the engineers presented a schematic of an actual bomb that he had designed. That plan was quickly axed and the proposal attributed to extreme sleep deprivation.

Each company’s top brass was scared. In February 2000 we met on neutral ground at a restaurant on University Avenue located equidistant from their respective offices. We agreed to a 50-50 merger in early March. We combined, raised a bunch of money before the crash, and had years to build the business.

E. If You Can, Run Away. If Not, Fight and Win.

If you do have to fight a war, you must use overwhelming force and end it quickly. If you take seriously the idea that you must choose your enemies well since fighting them will make you like them, you want wars to be short. Let that process go on too long and you’ll lose yourself in it. So your strategy must be shock and awe—real shock and awe, not the fake kind that gets you a 10-year war. You have to win very quickly. But since very often it’s not possible to ensure a quick victory, your primary job is to figure out ways not to have war happen at all.

Let’s return to the 2 x 2 matrix from class five. On one axis you have athletes and nerds. Athletes are zero sum competitors, and nerds are non zero sum collaborators. On the other axis you have war/competition and peace/monopoly capitalism. We said that a company should optimize for peace and have some combination of both nerds and athletes—nerds to build the business, and athletes to fight (and win) if and when you’re unfortunate enough to have to compete.

The nerds-athletes hybrid model allows you to handle external competition. But it also creates an internal problem; if you have to have at least a few very competitive people on your team, how do you avoid conflicts within the company? Very often these conflicts are the most disastrous. Most companies are killed by internal infighting, even though it may not seem like it. It’s like an autoimmune disease. The proximate cause may be something external. But the ultimate cause of destruction is internal.

When we overlay the noting of intracompany fighting on the Marx vs. Shakespeare framework, we get two theories as to why colleagues fight. Marx would say people fight internally because they wildly disagree about what the company should do, or what direction it should take. The Shakespeare version is precisely the opposite; people fight because they both want to do the same thing.

The Shakespearean dynamic is almost invariably correct. The standard version is that two or more people each want the same role in a company. People who want very different things don’t fight in well-functioning companies; they just go and own those different things. It’s people who want to do the same things who actually have something to fight about.

At PayPal, the center of conflicts tended to be the product team. David Sacks wanted the product to be a single seamless whole. That was a good approach, but a less good byproduct was that it was a recipe for product people overlapping with everyone else in the company. Product couldn’t do anything without infringing on someone else’s turf. A big part of the CEO job is stopping these kind conflicts from happening in first place. You must keep prospective combatants apart. The best way to do this is by making clear definitions and precise roles. Startups, of course, are necessarily flexible and dynamic. Roles change. You can’t just avoid internal war by siloing people away like you can in big companies. In that sense, startups are more dangerous.

PayPal solved this problem by completely redrawing the org chart every three months. By repositioning people as appropriate, conflicts could be avoided before they ever really started. The craziest specific policy that was enacted was that people were evaluated on just one single criterion. Each person had just one thing that he or she was supposed to do. And every person’s thing was different from everyone else’s. This wasn’t very popular, at least initially. People were more ambitious. They wanted to do three or four things. But instead they got to do one thing only. It proved to be a very good way to focus people on getting stuff done instead of focusing on one another. Focusing on your enemy is almost always the wrong thing to do.

III. Conversation with Reid Hoffman

Peter Thiel: How can people fall into the trap of fighting wars? Is there a strategy to avoid fighting altogether?

Reid Hoffman: To not get mired down is key. You must think very deliberately about your strategy and competition to do that. One element that I’d add to your comments is the very basic idea that part of reason we have competition is that people want resources. People need things, and very often they’re willing to fight to get them. Competition for resources can be natural, and not just a psychological construction.

Peter Thiel: The counter to that is that something like prestige, for example, isn’t any kind of scarce natural resource.

Reid Hoffman: But people value it a lot—so much so that they fight over it. As CEO, people routinely come and pitch you for new titles, with no substantive change in their responsibilities.

Peter Thiel: That’s true—there was a relentless escalating title phenomenon at PayPal. We had lots of VPs. Then lots of Senior VPs. In hindsight it probably wasn’t that stable. But we were acquired before anything really blew up.

Reid Hoffman: Back to your question—it’s so important for early stage companies to avoid competition because you can’t isolate it to one front. Competition affects you on the customer front, hiring front, and financing and BD fronts—on all of them. When you’re 1 of n, your job becomes much harder, and it’s hard enough already. A great founding strategy is thus contrarian and right. That ensures that, at least for an important initial time, no one is coming after you. Eventually people will come after you, if you’re onto something good. That might explain the Microsoft-Google competition you highlighted as sort of bizarre. Each has its great revenue model—its gold mine. At the start they were quite distinct. These respective gold mines allowed them to finance attacks on the other guy’s gold mine. If you can disrupt the other’s mine, you can take it over in the long run.

Peter Thiel: The criticism of that justification for competition is that the long run never really arrives as planned. Microsoft is losing a billion dollars per year on Bing.

Reid Hoffman: It’s possible that this playbook doesn’t work as well for tech companies as it used to. Search is an ongoing battle. But there are other successes. Look at Xbox. Microsoft’s decision to compete worked there. When Sony stumbled a bit, Xbox became a really viable franchise. Microsoft’s strategy is to own all of the valuable software on desks and other rooms, not just isolated products. So, with the Xbox, it’s made some headway in the living room. It’s complicated. But what drives the competition is the sense that there’s a lot of gold over there. So if you’re a startup and you find some gold, you can count on competition from all directions, including previously unlikely places.

Some competition is easier and that gives you more leeway. Banks, for instance, are very bad innovators, which turned out great for PayPal. In more difficult competitive scenarios, you really have to have an edge to win. Difficult competition with no edge makes for a war of attrition. People may get sucked in to ruthlessly competitive situations by the allure of the pot of gold to be had. It’s like rushing the Cornucopia in the Hunger Games instead of running away into the forest. Sometimes people justify this by rationalizing that “if we don’t fight it here, we’d just have to fight somewhere else.” Sometimes that’s a good argument, sometimes it’s not. But usually there’s a pot of gold that’s being chased.

Peter Thiel: But people are very bad at assessing probability. It’s irrational spend all your gold trying to get the other guys’ gold if you probably won’t succeed. I maintain that there is a crazy psychological aspect to it. It isn’t just rational calculation because tremendous effort is spent on things that, probabilistically, aren’t lucrative at all.

Reid Hoffman: It’s true that mimesis is a lot easier than invention. Most people are pretty bad at inventing new things. iPhones with a blue cover. Triangular card readers instead of square ones. That’s not invention. If you can actually invent good things, that’s the viable strategy. But most people can’t. So we see a lot of competition.

A side note on invention and innovation: when you have an idea for a startup,, consult your network. Ask people what they think. Don’t look for flattery. If most people get it right away and call you a genius, you’re probably screwed; it likely means your idea is obvious and won’t work. What you’re looking for is a genuinely thoughtful response. Fully two thirds of people in my network thought LinkedIn was stupid idea. These are very smart people. They understood that there is zero value in a social network until you have a million users on it. But they didn’t know the secret plans that led us to believe we could pull it off. And getting to the first million users took us about 460 days. Now we grow at over 2 users per second.

Peter Thiel: The very strategic focus on something no one was thinking of—business social networking—is one of the most impressive things about the LinkedIn. 460 days is moderately fast but not insanely fast. PayPal got to a million users in 4 to 5 months… [pause, laughter]. But while you always want to grow fast, you want to be able to grow more slowly. If you focus and target a non-competitive space, 460 days is plenty of time. You get more time to establish a great lead and then execute and maintain it.

Reid Hoffman: It’s obviously important to target an area that no one’s playing in. The interesting question is what do you do once you’re on everyone’s radar. You have to have some sort of competitive edge. Is it speed? Momentum? Network effects? It could be a lot of things. But you must think through it, because people will come after you as soon as you uncover value. You’ve found your gold mine; now you must defend it. It’s always easier for people to come take your gold than to find gold anew. You have to have a plan to dominate your market in the long run.

Social was big well before LinkedIn. It was something of a dogpile of competition for Linkedin in the early days. But the other companies who were focused on business social wanted to sell to enterprises. Enterprises, they thought, would build the networks. LinkedIn, of course, wanted to focus on individuals and stayed true to the vision. It’s scarily easy to lose sight of the big vision. People are always tracking down the CEO and telling doomsday stories about how we’re all dead if we don’t change something to address competitor x. If you start to focus on doing everything, you’re just going to war without any clear vision, and you’ll fail.

There’s also a version of this that applies to individuals. People look for individual gold—things like good career moves, prestige, status. Having multiple people competing for those things, is, as you said, a recipe for internal challenges.

At LinkedIn we addressed this by structuring precise roles, much like PayPal did. But unlike PayPal, we did this for teams, not individuals. Teams get mandates. A team is responsible for growth, mobile, or certain parts of platform. Sometimes the mandates overlap. Occasional conflict seems inevitable. But it’s kept manageable. The benefit is each team functions like a startup itself. There are clear goals and metrics. Every so often, you have to fix things and refactor things. That’s ok. Groups drift and different prioritizations can conflict. It’s worth it. In fact it’s probably a very bad sign if you don’t have to frequently refactor how stuff works to make it effective.

What’s key, as PayPal discovered, is that you give your people a path to success. Maybe they won’t fully agree with it. They don’t have to. There just has to be some reasonable buy-in. That is the best way to avoid internal conflict. The other route—just going full throttle on the us-vs-them dynamic—is very motivational too. But it has all the costs of war that theater that may not stay theater forever. It may defocus your long-term efforts, and, as Peter described, you get engineers designing bombs.

Peter Thiel: External war is a very effective way to forge internal peace. In early March of 2000, PayPal had $15M in bank. It was on track to run of money in 6 weeks. CFO Roelef Botha thought that this was quite alarming. He—quite sanely—shared his deep concern with everybody. But the engineering team wasn’t interested. The only thing that mattered was beating X.com. It didn’t matter if you went broke in the process.

Reid Hoffman: So you can’t just go into full war mode. You have to strategize as to how to avoid competition and external competition. That will take you far. But competition is inevitable. Even if you build good thing with network effects, people aren’t always smart. They’ll try to compete with you anyways, even if that’s a bad idea. So you have to strategize about how to deal with the forces of competition, too, both internally within the company and externally with other companies.

In the tech space, the landscape changes based on what technologies become available. Oracle and Siebel dominated enterprise software because they dominated the sales relationships. And then along comes the cloud. Now you have entirely new kind of products available for the same kind of functions. We’ve seen really massive companies being built in the last decade. SalesForce is the archetypical one that’s succeeded and gone public.

Peter Thiel: And SalesForce was funded by Larry Ellison to compete with Siebel on CRM. Then it succeeded and grew and now, of course, Oracle hates SalesForce.

Reid Hoffman: This plays into how the inevitability of competition. In tech, if you’re not continually thinking about catching the next curve, one of the next curves will get you. Yahoo owned the front end of the Internet in 2000. It had the perfect strategy. But it did not adapt; it failed at social and other trends; that didn’t go so perfectly. Just over a decade later, having missed some very key tech curves, it’s in a very different position.

Peter Thiel: Last class we talked about secrets. You want to have a secret plan. Probably not enough companies have a plan, let alone a secret plan. This gets complicated, because people’s secrets are secretive and so we might not know about them. But, with that caveat, what companies do you think have the best secret plans?

Reid Hoffman: Mozilla seems to have good plans. They understand the move from desktop to mobile. Different from classic companies, they’re not trying to build a closed franchise, but rather trying to keep open ecosystem for innovation. Quora has interesting plans about connecting people to knowledge. Dropbox is interesting, and probably has big plans that take it far beyond just being a hard drive in the cloud. The bottom line is if you don’t have a very distinctive, big idea—a prospective gold mine—you have nothing. Not all ideas work. But you have to have one.

Peter Thiel: A good intermediate lesson in chess is that even a bad plan is better than no plan at all. Having no plan is chaotic. And yet people default to no plan. When I taught at the law school last year, I’d ask law students what they wanted to do with their life. Most had no idea. Few wanted to become law firm partners. Even fewer thought that they would actually become partner if they tried. Most were going to go work at law firms for a few years and “figure it out.”

That’s basically chaos. You should either like what you’re doing, believe it’s a direct plan to something else, or believe it’s an indirect plan to something else. Just adding a resume lines every two years thinking it will buy you options is bad. If you’re climbing a hill, you should take a step back and look at the hill every once in awhile. If you just keep marching and never evaluating, you may get old and finally realize that it was a really low hill.

One reason people may default to not thinking about the future is that they’re uncomfortable being different. It is unfashionable to plan things out and to believe that you have an edge you can use to make things happen.

Reid Hoffman: People also underestimate how much of an edge you need. It really should be a compounding competitive edge. If your technology is a little better or you execute a little better, you’re screwed. Marginal improvements are rarely decisive. You should plan to be 10x better.

Peter Thiel: I recall being pitched on some anti-spam technology. It was billed as being better than all other anti-spam tech out there, which is good since there are probably 100 companies in that space. The problem was that it took a half hour to explain why it was allegedly better. It wasn’t as concise as: “We are 10x better/cheaper/faster/more effective.” Any improvement was probably quite marginal. Customers won’t give you a half hour to convince them your spam software is better. A half hour pitch on anti-spam is just more spam.

Shifting gears a bit: is there way to stay head of curve before it eats you?

Reid Hoffman: We ask prospective hires at Greylock how they would invest $100k between iOS and android, if they had to make bets about the future. The only wrong answer is 50-50. That is the only answer that’s basically equivalent to “I don’t know.” Think through it and take a position. You’ll develop insight. That insight—or more specifically the ability to acquire it—is what will keep you ahead of the curve.

Another huge thing to emphasize is the importance of your network. Get to know smart people. Talk to them. Stay current on what’s happening. People see things that other people don’t. If you try to analyze it all yourself, you miss things. Talk with people about what’s going on. Theoretically, startups should be distributed evenly throughout all countries and all states. They’re not. Silicon Valley is the heart of it all. Why? The network. People are talking to teach other.

Peter Thiel: It’s a trade-off. You can’t just go and tell everybody your secret plan. You have to guard your information, and other people guard theirs. At the same time, you need to talk and be somewhat open to get all the benefits you mentioned from the network. It can be a very fine line.

Question: Do people overestimate competition? What about the argument that you shouldn’t do x because Google could just do it?

Reid Hoffman: When I evaluate startups, that “Google can do it” isn’t really a valid criticism unless the startup is a search engine.

Google has tons of smart people. They can, in all likelihood, do exactly what you’re doing. But so what? That doesn’t mean you can’t do it. Google probably isn’t interested. They are focused on just a few things, really. Ask yourself: what’s more likely: nuclear war, or this company focused on competing with me as one if its top 3 objectives? If the answer is nuclear war, then that particular potential competitor is irrelevant.

Peter Thiel: Everyone develops an internal story about how their product is different. From outside perspective they often look pretty similar. So how can you tell whether what you’re doing is the same or whether it’s importantly different?

Reid Hoffman: You can’t systematize this. It’s a problem that requires human intelligence and judgment. You consider the important factors. You make a bet. Sometimes you’re right, sometimes you’re wrong. If you think your strategy will always be right, you’ve got it wrong.

Question from audience: Can you give some examples on how one can successfully get away from competition?

Peter Thiel: PayPal had a feature for feature competition with X.com that lasted intense 8 weeks. The best way to stop or avoid the war was to merge. The hard part was deescalating things post-merger. It was hard to immediately shift to being great friends afterwards. There is always a way in which things get remembered much more positively when everything works out in long run. Conversely, rivalries tend to get exaggerated ex-post when things don’t go so well.

Reid Hoffman: There was some pretty intense infighting at PayPal. One of the things that Peter has said is key: either don’t fight, or fight and win. But you should be skeptical that you will definitely win if you end up fighting.

PayPal’s biggest traction was with eBay. But eBay had an internal product called BillPoint. PayPal, as the sort of 3rd party disrupter, was at a serious disadvantage there. eBay was the only gold mine that existed. We had to win. It was time to leverage the athletes’ competitive talent. One decisive move in the war was focusing on e-mail. The real platform for auctions wasn’t the eBay website, as most people assumed. It was e-mail. People would receive emails when they won auctions. eBay knew this but didn’t understand its importance. PayPal, on the other hand, got it and optimized accordingly. Very often PayPal would notify people that they won the auction before eBay did! People would then use PayPal to pay, which of course was the goal.

It was much harder to compete against the Buy It Now feature. There, eBay had greater success roping people into paying with BillPoint. It was harder to get in front of people if they were just buying and paying for something right away on the website.

The takeaway advice is to always keep questioning the battle. Never get complacent. When you’re in battle, only the paranoid survive.

Question from audience: What do you think about the competition between Silicon Valley and New York? Reid, Mayor Bloomberg has argued that New York will become the dominant tech scene because the best people want to live there. He quoted you as saying “I don’t like all that culture stuff” and suggested that that view is “narrow.”

Reid Hoffman: I’m friends with Mayor Bloomberg, but I’ll return fire.

So Bloomberg is trying to make a tech-friendly New York that will compete and beat Silicon Valley. That’s great. We wish him the best of luck. More great technology innovation hubs within the US are great for us.

But, to compete, they’ll certainly need the luck. Silicon Valley has an enormous network effect. Tech is what we do. This is the game we play. If there’s anywhere in the world to go for tech, it’s here. People move here just to be a part of the tech scene.

The New York tech world has to compete for its technical people. Many of the best tech people go to hedge funds or move to Silicon Valley.

One of ways to understand effect of competition is companies that emerge here are competitive globally because crucible is so high. The best people go into tech here. And they have a single-minded focus about their work.

All the culture of NYC doesn’t matter positively or negatively, relative to succeeding at the technology innovation game. So it’s a wonderful place to live. Fine. Mayor Bloomberg, you’re very welcome to the people who want to live in New York for its culture and theater and operas. Personally, I love to visit. The people that we want are the ones who want to win this game first and foremost, and who don’t care terribly much about missing Broadway shows.

Question from audience: Isn’t culture important in a sense, though? Silicon Valley engineers aren’t social. So how can they make social games?

Reid Hoffman: It’s not that all great companies come from Silicon Valley. I was simply saying that it is extremely difficult to unseat Silicon Valley as the best place for tech companies. But certainly not every great tech company needs to be a product of the Valley. Indeed, that’s impossible. Groupon, for instance, couldn’t be created here. They need 3,000 salespeople. That is not the game that Silicon Valley specializes in. It worked very well in Chicago. So Silicon Valley learns from Groupon here; as did I. There are certainly other playbooks.

But the Silicon Valley playbook is a great, and perhaps the best. If you have to make a portfolio bet on technology or a portfolio bet on sales processes, you should take the tech portfolio every time. New York is the 2nd most interesting place for consumer internet. It’s just very unlikely to displace Silicon Valley as #1.

Peter Thiel: My take is that New York is a pretty distant second. There are some very cool companies coming out of New York. But one anti-New York perspective is that the media industry plays much bigger role there than it does here. That induces a lot of competition because people focus on each other, and not on creating things. New York is structurally more competitive in all sorts of ways. People literally live on top of each other. They’re trained to fight and enjoy fighting. Some of this is motivational. Maybe some of it is good for ideation. But it directs people into fighting the wrong battles. We will continue to see the more original, great companies coming out of Silicon Valley.

Reid, final question. What advice would you give young entrepreneurs?

Reid Hoffman: You can learn a lot from companies that succeed. Companies have benefited greatly from Facebook’s Open Graph. Ignoring that instead of learning it, for instance, could be catastrophic for you, depending on what you’re trying to do. But of course learning everything before you do anything is bad too.

The network is key. This is a large part of how you learn new things. Connect with smart people. Talk. What have you seen in last couple of months? What do you know? It’s not a go-and-read-everything strategy. You’d die before you could pull that off. Just exchange ideas with the smart people in your network. Not constantly, of course—you need to do work too—but in a focused way. Take what you learn and update your strategy if it’s warranted. And then keep executing on it.