By Amos Kareithi

The ear-shattering cacophony has reached a crescendo. Nearly every wall and tree along the main highways is sagging under the weight of the campaign posters.

As aspirants woo voters ahead of the March 4 General Election, let us listen to some muffled echoes from a similar poll held 55 years ago.

For the first time in 1957, indigenous Kenyans were granted an opportunity by the colonial authorities to participate in electing their representatives in what turned out to be an abridged version of democracy.

Interestingly, this momentous occasion took place in March 1957, when the colonial government consented to African members being elected to the Legislative Council.

The much-anticipated polls of 1957, just like the General Election, which has electrified the country, had been preceded by a tumultuous period.

This came after five years of anarchy, bloodshed and fear following the declaration of the State of Emergency, which started in October 1952.

The forthcoming elections are being held five years after the divisive 2007 General Election, which brought Kenya on the brink of anarchy and left more than 1,000 dead.

Even as the colonial Government cracked down on Mau Mau, a slippery organisation accused of fomenting war and rebellion in central Kenya, the Government still found time to cobble up a multi-racial constitution.

Colonial secretary Brainchild

Although there was no referendum unlike in 2010, which saw the passing of Kenya’s new Constitution, the supreme law drafted in 1954 was the brainchild of the then colonial secretary, Oliver Lyttleton.

The government in London and in Nairobi hoped, as Charles Hornsby explains in Kenya: A History since independence to introduce the Constitution after the State of Emergency ended.

This Lyttleton constitution was in support of racial segregation and provided for separate elections for each of the three races, Europeans, Asians and Africans.

According to the constitution then, the weight of each vote was determined by one’s colour, financial status and ethnicity, meaning a white man’s vote was superior to an Asian’s, while African was of little consequence.

Political activity ban

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

In fact, the law then was that Africans inhabiting Mt Kenya regions of central Meru and Embu were not entitled to vote as they were deemed to be sympathetic to Mau Mau and disloyal to the colonial government.

This explains why when other regions were allowed to form district-based political parties; the residents of areas dominated by Mau Mau were banned from forming a political party or engaging in any political activity.

The constitution provided that it was criminal and politically unacceptable for a political outfit to seek support beyond one tribe.

When Tom Mboya formed Kenya People’s Convention Party, the Government was outraged and forced him to change the name to Nairobi People’s Convention Party.

At the time, the registrar of political parties had enormous powers and could invoke Public Order ordinance of 1950 or societies Ordinance of 1952, and ban a political party if he was convinced it presented a threat to peace.

The elections were finally held after sham campaigns where the loyalty of each of the 37 candidates was tested before he could be cleared. Finally, only eight African representatives were elected.

The eight members of the Legco were supposed to represent the interests of nine million Africans compared to 54,000 whites who nevertheless controlled all instruments of Government.

Nurtured a revolution

Rather than risk allowing a Mau Mau sympathiser to represent Central Province, the colonial Government cleared Bernard Mate from Meru, who was ultimately elected at the expense of Eliud Mathu.

There was little controversy in other parts of the country where the first crop of African politicians were elected.

The colonial Government unwittingly nurtured a revolution through elections that propelled 46-year-old Oginga Odinga into national limelight.

He was elected to represent central Nyanza. Tom Mboya too, was elected to represent Nairobi and Ronald Ngala (Coast), Masinde Muliro (Western) and James Muimi (Eastern).

Despite the colonialists’ attempts to ethnicise politics by confining politicians and politics to tribal based districts, the newly-elected leaders formed African Elected Members Organisation (Aemo).

Sustained pressure

Aemo, under the chairmanship of Odinga, and Mboya as the secretary, gave the establishment nightmares as the members refused to join the Government between 1957-1958, and rejected the multi-racial constitution.

Their sustained pressure at one time saw 39 officials of Mboya’s political party arrested for incitement, but finally the Government conceded and scrapped the much-despised Lyttleton constitution.

It is against this background that a new Constitution named after the then colonial secretary Allan Lennox –Boyd was drafted.

The new constitution increased African representation to 14, equal to that of Europeans, while 12 special elected posts, four for each race, were created.

Again as fate would have it, the elections were held in March 1958 and provided the finalist list of the cast, which would finally shape Kenya’s destiny and steer the country to independence.

Mistaken belief

The new entrants included Jeremiah Nyagah (Embu–Nyeri), Justus ole Tipis (Maasai), Taita Towett and Julius Gikonyo Kiano for south Central.

Through machinations of divide and rule, the colonial government exploited the emerging fault lines between major and minor ethnic communities, which consequently split Aemo.

According to Hornsby at this time, the most credible person capable of leading Kenya was Mboya, a possibility that galled Odinga and Muliro who felt overshadowed and saw him as arrogant.

“Odinga started agitating for the release and rehabilitation of Jomo Kenyatta so that he could participate in politics. This call gained momentum and popular support across the country,” Hornsby writes.

At this time, whites were still trooping into the country in the mistaken belief that the earliest Kenya could gain independence was in 1975.

While Odinga and Mboya and other Legco members agitated for the release of Kenyatta who, with other five co-accused, were incarcerated at Kapenguria, the moderate Africans had other plans.

They teamed up with moderate whites who supported the scrapping of racism to form Kenya National Party, which heralded the death of Aemo in 1959.

On the other hand, African leaders were buoyed by the granting of independence to Ghana in 1958 and were convinced Kenya was on the threshold of self-governance.

The State of Emergency was finally lifted in 1960 and Kenyatta, his Kapenguria co-accused as well as more than 1,500 Mau Mau political detainees were released.

Fresh polls

In February 1961, another round of elections were held and this time, the African seats in the Legco had been expanded to 33.

During the polls, the turnout was a record 88 per cent or 885,000 voters out of which the dominant party then, Kenya Africa National Union (Kanu) garnered 67 per cent of all votes cast.

Despite having won the elections, Kanu declined to form Government after realising that the colonialists were not keen on releasing Kenyatta.

In the ensuing deadlock, Kadu formed a coalition with New Kenya Party and the Indian Congress Party to form the first African-led Government on April 18, 1961 under Ngala.

However, in May 1963, fresh polls were held and predictably Kanu won with 64 seats against Kadu’s 32. During the campaigns as is happening now, there was a lot of tension and the voters were allied to two major ethnic blocks.

Extensive intimidation

“The campaigns saw extensive intimidation and several deaths, but the polls were peaceful. In Isiolo, four people died from ethnic violence,” Hornsby says.

There are indications that foreigners heavily funded the elections. British intelligence agencies reported that Americans gave 40,000 Sterling Pounds through Mboya while, Russia contributed 70,000 Sterling Pounds through Odinga. India too, through Gama Pinto contributed 160,000 Sterling Pounds.

Ten elections later, the main pre-independence players who participated in the first polls are all gone with the exception of a few like Daniel Moi, who is now politically inactive.

Although the colonialists too, are gone, the foundations of the ethnic politics they founded are still intact as voters are divided along tribal lines and political parties draw their backing from these blocks.

Kenya too, has gone round a full circle and is scheduled to introduce a version of devolution first touted in 1959 by Ngala of Kaddu.

As the General Election clock ticks, Raila and Uhuru are fighting the political mind games started by Oginga and Mboya and furthered by Kenyatta during the cold war in the 1960s, although the ground has shifted.

And just like in the 1960s, the West is keenly watching the political developments, which have been influenced by the ongoing International Criminal Court cases.

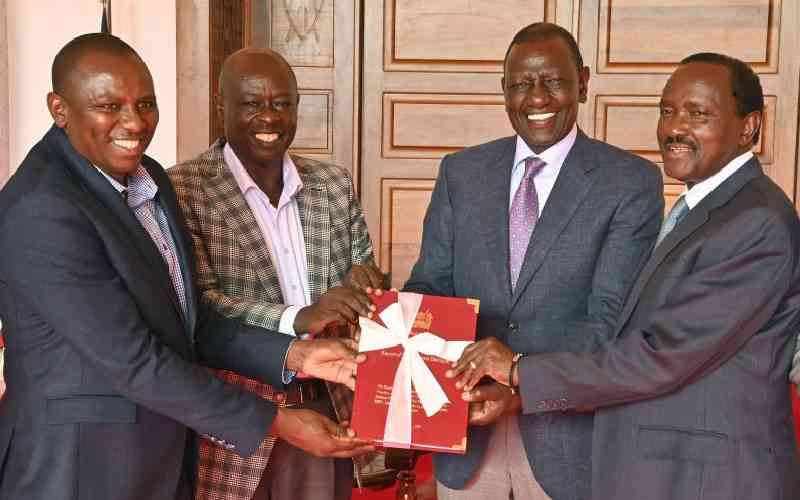

Kenyatta’s son, Uhuru is accused alongside his running mate, William Ruto of committing crimes against humanity. History has evidently repeated itself in more than one way.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.