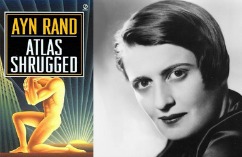

Atlas Shrugged Book Club, Entry 7: The Impotent Irrationality of John Galt

In the final, climactic part of Ayn Rand's novel, the mysterious John Galt gives his big speech. But is it revelatory or ridiculous?

The Atlas Shrugged Book Club will conclude early next week with entries by Conor Friedersdorf and Garance Franke-Ruta. Meanwhile, email your final thoughts on Part III of the book, or the novel as a whole, to conor dot friedersdorf at gmail for possible inclusion in the last round.

From: Jerome Copulsky

To: Conor Friedersdorf, Garance Franke-Ruta, Michael Brendan Dougherty

Subject: Part II

The crux of the Atlas Shrugged, the core of Rand's project, is John Galt's famous 60-page speech (roughly double the length of The Communist Manifesto), which can be regarded as a philosophy lecture or Objectivist sermon or Randian rant, depending on your point of view. In it, Galt presents his rationale for the strike -- a removal of sanction from the inverted morality of the "mystics" -- and his call to those to withdraw their support from the system, to join the strike themselves.

He thus ushers in the novel's Götterdämmerung.

It is right to focus on the speech, for, as I have previously mentioned, the novel is merely the vehicle for the message. (And, as we read in the "About the Author" statement, Rand means it!) Throughout the address, Galt depicts a world-historical contest of moralities, a battle between good and evil, life and death. (No shades of gray here.) On the side of darkness there are the mystics of spirit and the mystics of muscle, who would force individuals to serve a god or their neighbor; they are really two sides of the same coin; they are those who "preach the creed of sacrifice" and are "haters of man."

And then there is the side of goodness and light. Opposed to the parties of mystics are those like Galt himself, who regard man as a rational being, and whose morality is to serve oneself only. Reason, Rand asserts, leads to purpose and self-interest, which is the essence of virtue, and true human happiness. "Happiness," he explains, "is that state of consciousness which proceeds from the achievement of one's values" and is one's "highest moral purpose." Such a state of being is "possible only to a rational man." And the highest of such man is the productive genius, such as Galt himself. In this world, all human relations become transactional, commercial, as seen in the Randian utopia of Galt's Gulch, where even borrowing your buddy's car for an afternoon will cost you. "There are no conflicts of interest among rational men," Galt confidently remarks at one point. "When I disagree with a rational man, I let reality be our final arbiter." Galt's embrace of this true morality leads him to his political stance, an endorsement of a minimal state:

The only proper purpose of a government is to protect a man's rights which means: to protect him from physical violence. A proper government is only a policeman, acting as an agent of man's self-defense, and, as such, may resort to force only against those who start the use of force. The only proper functions of a government are: the police, to protect you from criminals; the army, to protect you from foreign invaders; and the courts, to protect your property and contract from breach or fraud, to settle disputes by rational rules, according to objective law.

The myriad problems raised by such a conception of a state should be obvious to anyone who thinks seriously about politics and property and power. In the rough and tumble of the real world, things are rarely as simple as Galt imagines them to be. There is, first of all, the question of what is meant here by "force," and what it means to commence with it. But one can then ask about the how the power of defense is to be organized; how big the military should be; who constructs the roads and bridges that it will use; how to regard the externalities of human activity such as, say, pollution; what should be the method of paying for such protection.

The problems go on and on.

I want to note, however, that Galt regards this as a description of America's original political system, which he hopes to reestablish. I was rather struck by the notion that Rand's project was essentially restorative, that she saw a perfect coincidence between her ideas and the Founders. I trust that many readers find this claim preposterous. For starters, Galt states that America's system was founded on the premise "that man's life, his freedom, his happiness are his by inalienable right." This language is undoubtedly a paraphrase of the Declaration of Independence, but with a significant omission. For Jefferson, of course, people are endowed by their Creator with "certain unalienable Rights." (It's also worth mentioning that Jefferson saw the pursuit of happiness as one of these Rights, whereas Rand seems to have made happiness a right unto itself.)

There is, however, no room for a Creator God in Rand's materialist universe. Rand never indicates how human beings come to be, but it is clearly not from some beneficent Judeo-Christian deity. Rand also rejects the idea that rights are established by human convention, granted by states or by law. So from where, then, do such rights originate? Perhaps sensing this problem, Galt/Rand states that "Rights are conditions of existence required by man's nature for his proper survival." There is a lot packed into that sentence -- what is meant by "conditions of existence"? What is human nature? What is his "proper survival"? -- but although Galt drones on for hours (the text says for three, but I suspect that his speech would have gone on for much longer), he does not, to my mind, clear up these matters to any satisfaction. The claim about the origin of rights is simply asserted, not demonstrated. (In fact, this is my overall feeling about Galt's speech: "Reason" is used more as a rhetorical device -- to force the reader to submit to its positions -- than as a mode of argumentation.) I suppose someone with more patience for this book than I have could wade through Galt's muddled metaphysics and establish just how "the law of identity" leads to property rights, but remember that, in the plot of the novel, Galt's speech was a revolutionary act meant to inspire his listeners, undermine the regime of the looters, and usher in the reign of the Galtians; it was not a text to be brought to the seminar room and pored over by graduate students, but a call to arms. Or rather, a call to drop out.

Since I brought up human nature, there is also the matter of the thinness of Rand's anthropology. Rand's basic assertion is the rationality of human beings. (To the extent that a person is irrational, he is regarded as evil, anti-mind and anti-life.) And it is this conception of the human being as a rational, thinking being which leads to her ideal of the productive genius, his happiness, and the political order that would protect and preserve it. For Rand, the state only exists to shield the rational from the irrational, the good and the strong from ravenous desires of the wicked and the weak.

Of course, other rationalists have drawn strikingly different conclusions. In this regard, it useful to note that much serious political philosophy proceeds from a completely different premise -- the imperfect rationality of human beings -- and rightly so. If one considers Hobbes, say, or Spinoza, or Locke, three of the thinkers who inaugurated modern liberalism, one will notice that the fundamental problem of social life is that human beings are driven by their passions and their imaginations, by their hopes and their fears. It is these passions that create the problems and tensions that point to the need for stable political organization. While it is reason that leads them to enter into civil society -- to escape from the inconveniences of the state of nature -- the political order arranged is one that must take human beings as they are and not as the best they could be. This could be an authoritarian state, as it was for Hobbes, or a liberal democracy, as it was for Spinoza. In both cases, however, there is the recognition that human beings are passionate creatures, that the state is needed because of the problems inherent in human nature, that these problems may be alleviated somewhat in civil society but they won't go away.

Ironically, when one mulls it over, one may find that it's Galt and his band of strikers and dropouts who prove to be driven by their passions. Galt especially, who, despite his ultra-handsome looks and heroic self-understanding, can't muster up the gumption to just go up to the woman he has a massive crush on and ask her out for a drink -- or at least just talk to her -- and instead sits around chatting up her poor, love-struck assistant, hoping to catch a glimpse into her life.

Is this rational action, heroic action?

No, I think not. And aside from being somewhat creepy, it underscores the true impotence of Rand's hero. And it's not only with Dagny. When faced with the "communist" takeover of the motor factory, Galt doesn't seek out the banker Midas Mulligan and ask for a loan so that he can develop his motor on his own or attempt a run for political office; he just takes his toys and goes into hiding, hoping by such action to help hasten the apocalypse. This seems to me to be more like the behavior of a petulant adolescent than of the "highest man." Galt longs for a total transformation of human society, a complete victory for his higher morality and the unconditional surrender of those who oppose him, and he is content, indeed happy, to watch everything be destroyed to get there.

And the attempt to flee from reality courses through Rand's novel, from the disappeared and the destructive activities of Francisco D'Anconia and Ragnar Danneskjöld to Dangy's fruitless affair with Hank to the libertarian fantasyland of Galt's Gulch. Despite all of their speeches and protestations, these people are not so much stern rationalists but romantics. Such characters make terrible role models for those of us who are forced to reside in the world, which just may not be the stage for the struggle between the looting mystics and heroic individuals, but a place infinitely more complex, and more interesting. (Also, we should keep in mind that it is people convinced of their superior rationality and gnostic insights into the direction of world-historical change that generally pose the greatest challenge to the stability of the political order.)

It is worth remarking, too, that there is no sense of tragedy, no sense of the ultimate fragility of existence, in Rand's work. Her heroes regard suffering as something unnatural and unnecessary, and happiness as the only rightful condition of man. It is a strangely sterile world, one without sickness or disease or disability, where failure (in business) is merely an incentive to greater striving, and death takes only the villains, the marginal, or the vast unnamed. Rand's heroes are unencumbered by finitude, however. They strive to overcome "the contradictory, the arbitrary, the hidden, the faked, the irrational in men," to recover, as Galt himself says, the spirit of their childhood. There is a word for people who try to escape from the contradictory, the arbitrary, the irrational and tragic dimensions of life that we all must face--that word is delusional.

From: Michael Brendan Dougherty

To: Conor Friedersdorf, Garance Franke-Ruta, Jerome Copulsky

Subject: Part II

Bill Buckley once said he thought Whittaker Chambers had gone too far when he wrote in his review of this book, "From almost any page of Atlas Shrugged, a voice can be heard, from painful necessity, commanding: 'To a gas chamber -- go!'" I've been reading the book with an eye toward Chambers' judgement.

Shortly after we are introduced to John Galt, he solemnly intones these words: "Ever since I can remember, I had felt that I would kill the man who'd claim that I exist for the sake of his need -- and I had known that this was the highest moral feeling."So, Chambers was right. And I hate to be the outside-it-all religious one here, as always, but this really is a repulsive thing to put as the highest moral feeling. This is John Galt talking about the looters and moochers, the takers. Shiftless employees, socialists, etc. His long speech is fascinating; it is also so humorless. None of these heroes has any lightness of spirit. They are so leaden. Galt eventually addresses his inferiors as "you who dread knowledge" and shortly thereafter informs them "You have nothing to offer us. We do not need you ... Are you not crying: No this was not what you wanted?"

And I really wonder where the disabled, the sick, the ignorant, and all manner of humans fit into Ayn Rand's vision. These of course are the people that will starve first under the strike of the abled. So while violence is officially abjured by these Objectivists, you do get this sick sense reading the text that Randians would love to just execute a load of "inferior" people. What is a palsied man but a perpetual taker? Give him a bullet, he takes no more. This is never made explicit, but the feeling of it just oozes from everywhere.

And yet again, there is a small something in me that wants to excuse these excesses. The Soviet Union really did do monstrous things to achieve its plans, using brute force, show trials, and the most insane sort of economic planning. And Rand's own escape from Russia to America has to be a part of her narrative of the super-capitalists withdrawing their talent from the monster state. Her talents were not drafted in service of that corrupt and deformed worker's state. I find her impression that some people like a tyranny depressingly convincing.

But the sympathy ends. John Galt at one point explains how to fix a torture machine currently being used on his own body, in order to destroy the torturers. And when he gives his blessing to the new world he is about to build, he makes a dollar sign in the air. I haven't burned the book, but I did throw my iPad down into a cushion at this exact point.

I couldn't agree more with the point Jerome makes about the shallowness of Rand's anthropology. You get pleasure and pain, joy or suffering and that's it. Men of reason don't disagree? Who are these men of reason? Even if we accepted all of Rand's premises, Reardon, Dagny Taggart, and even John Galt himself seem absolutely transported and taken (with themselves) at times. My own view is that enterprise and competition are necessary evils. I think it helps man to remove himself from the commercial sphere as much as he can, and it is obvious that this is what some of the "men of the mind" want this for themselves as well. Some of those in Galt's Gulch are effectively retired on their riches.

Naturally, Galt rants against the one Christian doctrine that is essentially proved by a reading of history: Original Sin. It is said to be a "cowardly evasion" that man is born with free will but with a tendency to evil. Galt rejects this idea, dismissing it by saying that it makes men like loaded dice. And yet, everything we know from psychology, sociology, sociobiology, history, and self-reflection tells us that we want shortcuts, we want power, we are burdened by our genes, our upbringing, our social environment, and that these are powerful forces, though we often feel at the same time that they are not determinative. And business is not rational. Even the best businessmen favor their friends and family; they favor those like them. They do not come to some reasonable conclusion about the wages of their employees, and the employees do not come to reasonable conclusions. They fight, cajole, prey upon, and exasperate one another in negotiations. If so many humans can be taken in by a lying morality, one so obviously fraudulent and tyrannical, why you might think there was something a little warped about human nature, no?