An engineer's quest to caption the Web

- A deaf engineer at Google is trying to use technology to bring captions online

- The vast majority of online video does not have closed captions for the deaf

- The FCC requires captions for most TV programming but not for Internet video

- Engineer says being deaf has empowered him to be a better worker

Mountain View, California (CNN) -- The Internet used to be a place where Ken Harrenstien could do anything.

The Google engineer, who has been deaf since childhood, loved the Web because he could e-mail and chat without the aid of a sign language translator.

But as the Web evolved and got faster, online video started to flood in. And all of a sudden, this place that once allowed for limitless communication started to feel walled off to Harrenstien.

"It was only when they started adding videos that the Net was not my means of access, but it became a barrier," he said in a recent interview, speaking through signing interpreter. "And that was very frustrating."

The reason for Harrenstien's trouble is simple: Almost no video on the Internet comes paired with text captioning for the deaf.

While the U.S. Federal Communications Commission requires closed captioning for nearly all television programming, the same isn't true for online video.

But Harrenstien isn't sitting back and complaining. He's dedicated his career at Google to developing technology to bring closed captioning to the Internet.

It's a quest informed by personal experience. Harrenstien says his work is a reminder that being deaf isn't a limitation. It's empowering.

--Ken Harrenstien, Google

"It is extremely important [to my work] because I'm creating something I want and need for myself," Harrenstien said in a second interview, conducted through an Internet chat program.

"So, I can identify very well with all of the other people who similarly need and want this. ... This sometimes helps me keep going in the face of frustrations."

Personal quest

When Harrenstien was 5 years old, he had a nightmare that changed his life.

He'd become sick with a high fever and the mumps. He went to sleep one night with the ability to hear. When he woke up from a terrifying dream, he was deaf.

"As I recall, the dream was scarier" than waking up deaf, he said.

Throughout his career and personal life, Harrenstien has found ways that being deaf is an advantage.

He met his wife, for instance, because she saw him using sign language. At the time, she was training to be a sign language interpreter. They bonded over their mutual love for ice skating, and the couple now has three children.

Being deaf also has guided Harrenstien's work.

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harrenstien worked on a projected called the ARPANET, which was one of the first versions of e-mail and online communications.

"I was motivated because I wanted that system to exist so I could communicate with people," he said.

He went on to help develop a project called Deafnet, an early online community and messaging tool for deaf people.

Machine captions

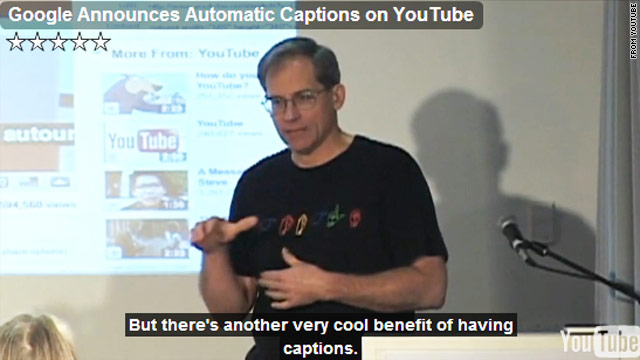

Harrenstien is now at Google, and he and a team of other engineers have created automatic captioning for a handful of educational channels on YouTube.

That technology debuted in November 2009. It works by interpreting the sound on a video clip, translating that data into text, then adding the text on top of the video at the appropriate times.

It's a tricky feat, and Harrenstien is the first to admit that the technology botches some voice-to-text translations.

But he still sees these "machine-generated" text captions as a major step toward making the Web equally accessible to all people.

He also works on awareness.

There are more deaf Internet users than Italian speakers, and nearly as many deaf people are online as those who speak French and Korean, according to Google. But many people who aren't deaf don't realize that online video isn't already captioned, or that so many people rely on captions to watch video, he said.

Google is also working to make it easier for people to upload captions of their own, and the company is encouraging people who upload video to the Internet to use its software to easily input captioning for deaf people.

When people who own videos on YouTube upload text transcripts, Google's auto-captioning technology will put the text on the video without time codes.

Harrenstien said the Web would become more accessible if everyone pitched in to help bring closed captions to online video clips. Some YouTube channels already have captions, including presidential addresses from the White House.

"What I would like to see happen is that people would see what we are doing here, and realize, 'Oh, this is really useful,' and all start doing the same thing,' " he said.

Meanwhile, new video -- most of which is not captioned -- continues to flood the Internet at an incredible pace.

In a presentation at Google headquarters, Harrenstien showed a video clip of a roaring waterfall as he said that more than 20 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute.

That's more than three years of video uploaded in a day.

Computers will have to help humans to caption all of that backlogged video, Harrenstien said.

Caption regulation

It wasn't all that long ago that television programming was inaccessible to deaf people.

Harrenstien remembers occasionally watching TV before it had captioning, just to get a sense of what the medium was like.

But overall, he found TV to be a waste of his time until Congress in 1996 forced broadcast companies to caption the majority of their programming.

He says captions wouldn't be on TV today if the FCC hadn't required it, but he stopped short of saying the federal government should require captions on all online video.

Dianne Stark, an administrator with the Described and Captioned Media Program, a nonprofit that works on media accessibility issues, said the federal government should require captions for online video.

She praised Google for its work on auto-captions but said people who post videos online should upload accurate captions so their work is accessible to deaf people.

"We are delighted that Google has tried to perfect this speech-to-text because it's a start," she said. "However, if you have 10 percent errors, and that's just an estimate, it can change the content entirely."

She added: "I think the difficulty with Google is sound recognition. [Caption accuracy] depends on who the narrator is. It depends on if the narrator has a Southern accent of a Northeastern accent or whatever. It's more difficult for the speech recognition to be precise."

The FCC did not return phone calls or e-mails requesting comment.

Harrenstien is trying to combine caption technology with awareness to make online video more accessible -- with or without regulation.

After closed captioning came to TV, Harrenstien said he took to science fiction programming because he "wanted to see what the future would look like."

Maybe he will be able to watch some of those programs online soon.