How do we design scientific research to have impact in the world?

TNC conservation scientist conducting research at the Garcia River Forest in Northern, CA. Photo: © Bridget Besaw

Scien tists devote substantial time and resources to research intended to help solve environmental problems. Environmental managers and policymakers must decide how to use the best available research evidence to prioritize actions leading to desired environmental outcomes. Yet decision‐makers can face barriers to using scientific evidence to inform action. They may be unaware of the evidence, lack access to it, not understand it, or view it as irrelevant. These barriers mean a valuable resource (evidence) is underused.

tists devote substantial time and resources to research intended to help solve environmental problems. Environmental managers and policymakers must decide how to use the best available research evidence to prioritize actions leading to desired environmental outcomes. Yet decision‐makers can face barriers to using scientific evidence to inform action. They may be unaware of the evidence, lack access to it, not understand it, or view it as irrelevant. These barriers mean a valuable resource (evidence) is underused.

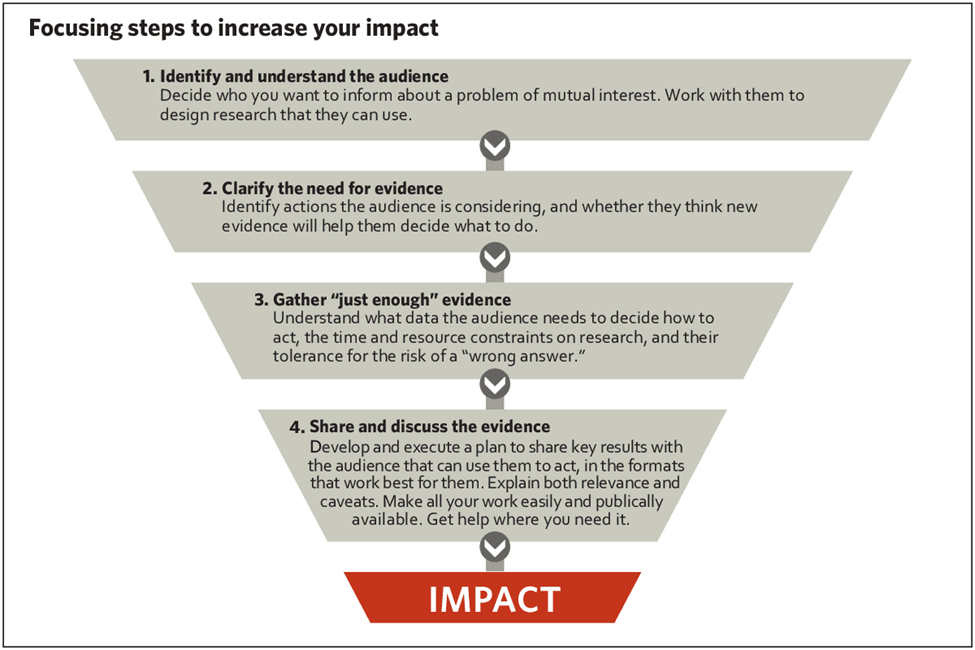

The authors of a paper in Conservation Science and Practice provide a set of practical steps for scientists who want to improve the impact their research has on decision‐making. These steps are outlined below and a summary can be downloaded here.

There are also two interviews about the paepr (from OCTO and Cool Green Science), a science brief, and a recording of a webinar about the research.

Often the audience will have potential actions in mind, at specific spatial and temporal scales. Researchers should identify the actions being considered. If lack of evidence is a barrier to deciding how to act, researchers should determine what evidence would motivate and empower the audience to act. Develop research questions in partnership with the audience and should seek to understand the political and economic context, and respect the legitimacy of how the audience makes decisions.

Jonathan R. B. Fisher, Stephen A. Wood, Mark A. Bradford, Rodd Kelsey